Country Report

Évaluation Nationale du Moniteur: Australie

L'Australie célèbre la diversité, mais dans la pratique, l'histoire coloniale et l'exclusion limitent l'évolution du pays vers le pluralisme.

Overall Score: 6

This assessment was completed in 2021.

Australia is a burgeoning multicultural country. Over half of its population is either born overseas or has at least one parent born overseas. However, the country’s relationship with diversity has been challenging. Stemming from its legacies of colonial settlement, the country has wavered between a policy of multiculturalism which celebrates diversity and one of ‘mainstreaming’, where individual newcomers are responsible for adjusting to Australian values and ways of life. In focussing on three distinct groups: Indigenous Australians, Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Migrants, and Temporary Migrants, the report underscores Australia’s attempts to move from its settler-colonial roots towards a society that is more inclusive for all members.

In Australia, systemic inequalities and exclusions undermine progress towards achieving pluralism. While the country has many international treaties and protocols in place, some group-based inequalities and discrimination may eclipse existing policies that are intended to support minority groups. Furthermore, significant gaps exist in policy implementation, data collection, gender-based and economic equality, private sector equality, institutional trust, judicial neutrality and the accessibility of civil society organizations for minority communities. For many minority communities, a sense of shared ownership in Australian society is out of reach, even while there is, overall, a strong desire to belong in Australia. Together, this report reveals a mixed approach to pluralism, one that celebrates pluralism as a concept but stops short of taking the substantial actions that would improve the prospects for pluralism and affect Australian patterns of life.

I. Commitments

For pluralism, commitments are the most prominent way for states to declare their intent to build inclusive societies, and for non-state actors to keep states accountable. Commitments to pluralism can anchor other efforts to make society’s hardware and software more inclusive.

1. International Commitments

Average Score: 6

Indigenous Australians | Score: 5

CALD Migrants | Score: 7

Temporary Migrants | Score: 5

Australia has signed and ratified the following international human rights protocols which affect minority groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (henceforth Indigenous Australians), culturally and linguistically diverse CALD background migrants, and temporary migrants. These treaties and protocols include the following:

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (signed 1948, ratified 1949, but genocide was not a crime in Australia until 2002).

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) (signed 1966, ratified 1975). ICERD has since yielded some impactful complementary laws in Australia, including the Commonwealth Racial Discrimination Act 1975 and the Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act 1984. These acts implement some but not all rights for women contained in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (signed 1972, ratified 1975).

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (signed 1972, ratified 1980). Australia remains the only democracy not to have legislated the ICCPR’s instruments into law. It has used the ICCPR instruments to support other conventions including ICERD.

- Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and Protocol Relating the Status of Refugees (ratified 1954, protocol 1973). Australia agreed and is bound to the standards of protecting refugees. It further incorporated the Migration Act 1958 into its domestic legislation as its obligation to protect refugees. However, Australian asylum-seeker policies continue to be subjected to marked international criticism. In the recent 2021 Universal Periodic Review at the United Nations Human Rights Council, 47 UN member states challenged Australia’s refugee and asylum policies and submitted 50 significant recommendations including Australian’s offshore processing and the indefinite detention of children and asylum seekers.

- CEDAW (signed 1980, ratified 1983).

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (signed 1990, ratified 1990). Australia’s obligations in implementing the CRC have been slower than expected. The CRC treaty reserves special rights for children. Australia agreed to complement the CRC with the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict and the Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography as well as other treaties important to protect children’s rights, such as the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT).

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (signed 2007, ratified 2008).

- The Optional Protocol to OPCAT (signed 2009, ratified 2017). The ratification of OPCAT further reinforces Australia’s commitment to the universal human right for children in preventing torture and mistreatment. OPCAT allows a network of Australian inspectors to monitor places such as juvenile and immigration detention centres and prisons. Additionally, the ratification allows the United Nations (UN) Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture to periodically monitor the rights of refugee children in detention and people deprived of liberty. However, Australia has yet to implement its instruments into laws, policies and practices. The Australian government also continues to draw international condemnation for holding children as young as 10 years old criminally responsible, with many Indigenous youth being arrested by police, remanded in custody, convicted by the courts and imprisoned. In 2019, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended 14 years as the minimum age of criminal responsibility.

Australia has declined to sign or ratify the following protocols:

- International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families. This is an important covenant that Australia has yet to ratify. The decision by Australia not to ratify the Covenant was viewed through the lens of domestic laws instead of international laws. Efforts from the international community failed to encourage Australia to ratify it. Australia argues that not only is this convention not compatible with its domestic migration policies but also migrant workers are protected by domestic laws such as the Age Discrimination Act 2004 and the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, the Fair Work Act 2009, the Migration Legislation Amendment (Worker Protection) Act 2008 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1984.

- International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. Only 23 member states (none from the Anglosphere) have ratified this (1989) convention endorsing self-determination and rejecting integrationist/assimilationist approaches.

- UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: As a member state at UNESCO’s General Conference, Australia voted for the Convention’s adoption in 2003, but it is still not a state party to the Convention, despite its importance in Australians’ commitment to the preservation of cultural and traditional rights of Indigenous peoples, migrants and the environment.

- UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions.

- Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2013).

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a communications procedure (2014).

- International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (2010).

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) monitors and provides independent reports on how Australia is meeting its national and international human rights obligations.

At the governmental level, a long-standing suspicion of, and a deep-seated resentment towards, UN interventions in or commentary on Australian matters (especially, on the conservative side of politics) prevails.

2. National Commitments

Average Score: 6

Indigenous Australians | Score: 5

CALD Migrants | Score: 7

Temporary Migrants | Score: 6

Australian states and territories have legal frameworks that grant diverse groups complete and equal civil and cultural rights. Most of these legal systems, including law enforcement agencies are, however, overshadowed by the lack of confidence in them among minority groups. Purportedly, for most Australians, the orthodoxy of liberal democracy, and the supposed independent judiciary system and media have underpinned their political stability and prosperity substantially protecting their basic rights and freedoms. However, this is not true for all Australians.

Right to Exist

Despite Australia’s signing and ratification of several conventions which, to an extent, are part of Australian law, Indigenous People continue to live with ramifications emanating from the lack of full protection of their basic human rights and freedom. This is evident in their low quality of life and inequalities in education, health, housing, jobs, land and the environment. Systemic racism and discrimination against the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are marked in the Australian legal systems with the comparatively high level of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders engagement with different areas of the legal system. Some of these include the criminal, child protection and welfare systems.

The AHRC recommending recognition of Indigenous People in the Constitution is the first step in ensuring protection and fostering pluralism in Australia. The recommendation also highlights that reformation of the Constitution should remove discriminatory provisions and replace them with a guarantee of non-discrimination and equal treatment.

This is despite Australia’s anti-discrimination laws (including on racial age, disability, sex and religion) that also seek to ensure the rights of minority groups are protected.

In 2008, a national apology was made to Indigenous people and, especially, the Stolen Generations, for the suffering they endured.

Native Title legislation (1993, amended in 1998, 2007 and 2009) that clarified the legal rights of landholders and the processes that must be followed for native title to be claimed, protected and recognized through the courts, increased recognition of Indigenous rights. A 2013 report found that Indigenous peoples’ interests are recognized formally through agreements or land title in well over half of Australia’s land area. But, at the federal level, progress has been very slow. In 2021, the federal government announced a $378 million (AUS) reparations scheme for Stolen Generations survivors in the Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory, and it called on the Western Australian and Queensland governments to similarly compensate Indigenous people. Indigenous Australians have embarked on a campaign for national reconciliation and constitutional recognition as the First Nations of Australia (described further below).

Right to Non-discrimination

Australia does not have a bill of rights, and there is no equal protection clause in the Australian Constitution; attempts to introduce one have failed. There have been only five cases in which Section 116 has been tested in the High Court. In each, the Court narrowly interpreted establishment and free exercise. In short, where a free expression of religion conflicts with a state interest, the state prevails. And the state may engage with religion in any way it chooses short of aiming to establish any religion or setting religious tests for public offices. Generally, throughout Australia, it is unlawful to discriminate on the basis of age, disability, race and gender in public life, including education and employment.

The lack of a bill of rights is offset by a web of statutory protections at the federal, state and territory levels.

The Fair Work Act 2009 (Commonwealth, or Cth) covers all employees in Australia, including temporary migrants. It provides powers of investigation and enforcement of compliance regarding workplace rights and obligations and provides information in different languages. In 2013, the Australian government established national Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender. The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 prohibits discrimination based on people’s colour, immigration status, country of origin or ethnicity. The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 seeks to provide equal opportunity to men and women in Australia and affects Australian international human rights obligations. The act was amended in 2013. The Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender identity, and Intersex Status) Act 2013 makes it unlawful to discriminate on a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. Under this act, same-sex couples are protected from discrimination under the definition of “marital or relationship status.” The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 prohibits discrimination based on people’s disabilities and applies to education, access to public spaces, employment and the renting and buying of houses. This act covers people with temporary and permanent disabilities. The Age Discrimination Act 2004 forbids discrimination based on age. Complimentary anti-discriminatory laws also exist at the state and territory levels and operate concurrently with the federal government laws prohibiting discrimination based on age.

The situation regarding religion is more complicated. There are no laws at the federal level that widely forbid discrimination based on religion and beliefs in public life. Religious bodies and educational institutions enjoy some protection under the exemptions to the provisions of the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) and the Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth). The Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 provides some limited protection, empowering the AHRC to act on a complaint about religious discrimination in places of employment and can investigate complaints about acts or practices that violate freedom of religion or belief. However, its recommendations are non-binding and cannot be directed to a court. The Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) prohibits employers from discriminating against people in the workplace on the basis of their religion. Most states and territories prohibit discrimination on the basis of religious belief within their anti-discrimination laws.

In the past five years, protection of freedom of religion has been the focus of a number of federal political processes, which led to the passing of the same-sex marriage bill in 2016. The review led to the government drafting the Human Rights Legislation Amendment (Freedom of Religion) Bill 2019, which is presently at the second exposure draft stage.

Anti-vilification provisions were incorporated as Part IIA (including Sections 18C and 18D) of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) through the Racial Hatred Act 1995 (Cth). Though subsequent governments have sought to limit these, particularly 18C and 18D, they were abandoned due to sustained public opposition and parliamentary defect.

While these attest to the Australian public’s abiding acceptance of anti-hatred laws, they also highlight how ethnic minorities’ sense of acceptance and belonging is still largely tied to the legal protections against discrimination.

These campaigns to reform the Racial Discrimination Act are part of a broader conservative and civil libertarian objection to the work of the AHRC, namely that it is preoccupied with social justice issues.

Right to the Protection of Identity

Australia has mostly resisted recognition of Aboriginal customary law. The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC, 1977–86) inquired into Aboriginal customary law and recommended that customary law be recognized in several areas, including criminal investigation and criminal law, traditional marriages and children, hunting and fishing and broadly on matters of recognition. However, it recommended against establishing Indigenous courts. Implementation has proven painfully slow, as detailed further in Section 4 on Policy Implementation below.

Furthermore, there have been five national multicultural policy statements. While successive Australian governments have lent their own emphases to the development of multiculturalism policies and brought varying degrees of enthusiasm to the task; all but the last policy statement incorporated, in some form, the same four provisions. These are the right of all Australians to maintain their cultural identities within the law; the right of all Australians to equal opportunities without fear of group-based discrimination; the economic and national benefits of a culturally diverse society; and respect for core Australian values and institutions—reciprocity, tolerance and equality (including of the sexes), freedom of speech and religion, the rule of law, the Constitution, parliamentary democracy and English as the national language.

Two important caveats apply. First, as noted above, the states and territories have pursued multicultural policy through legislative acts, charters, policy frameworks and funding. Second, many legacy multicultural policies and institutions remain in place, among them the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), the Multicultural Access and Equity Policy, and the National Ageing and Aged Care Strategy for People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds.

Temporary migrants can access some but not all multicultural provisions. Some provisions, such as certain public interpreter and translator services, can only be accessed on a fee-for-service basis (see Section 14).

Right to Participation

Australians have rights to participate, notwithstanding the absence of a bill of rights. As noted above, extensive laws at the federal, state and territory levels protect against discrimination. Australians are compelled to participate in voting to elect federal and state (and, in some jurisdictions, local) representatives, completing the census and undertaking jury service if summoned.

Affirmative action has had some limited applicability in Australia. The main legislative instance was the Affirmative Action (Equal Opportunity for Women) Act 1986 (Cth). The Act was replaced by the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999 (Cth) and again reviewed and replaced by the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 (Cth). In public sector employment, the Public Service Act 1999 (Cth) offers commitments to non-discrimination and respect for diversity and people of all backgrounds in the context of a merit-based employment process (see Section 6). Today, many higher education institutions and non-public employers encourage applications especially from women and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Participation in mainstream political parties has elicited debate over the need for affirmative action. Initiatives by the Australian Labor Party (ALP) mean female representation is near parity for the party across the federal and state parliaments. The Liberal Party has consistently rejected affirmative action as a means for improving its female representation and has little more than a quarter of women across all Australian parliaments (see Section 6 for further discussion).

Temporary residents and migrants are generally excluded from all such rights to participation, at least on the same terms and conditions enjoyed by citizens and permanent residents.

The only collective self-government rights that apply under Australian law are those devolved to the states and territories. A quasi form of self-government was the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission that operated from 1990 to 2005. A body comprising Indigenous appointees, it was tasked with advising the government on matters and decisions affecting Indigenous communities. In 2017, the First Nations National Constitutional Convention issued The Uluru Statement from the Heart, an outcome of a national process of deliberation on suitable constitutional recognition for and by Indigenous Peoples. The Uluru Statement calls for incorporating a “First Nations Voice” in the Australian Constitution, and a Makarrata Commission to oversee a process of agreement-making and truth-telling between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Uluru Statement was rejected by the government on the grounds that it would amount to a third chamber in Parliament. The campaign for recognition continues, notwithstanding considerable political resistance.

Gender and Sexual Orientation

In 2017, the Marriage Act 1961 was amended to respect marriage equality and now defines marriage as “the union of 2 people to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life.” The reform followed a difficult political process between public support for marriage equality and the ardent opposition of conservatives within the government coalition. A problematic public plebiscite, wherein rights were put to referendum, discriminating against same-sex couples, led to the change with 7,817,247 (61.6 percent) responding “yes” and 4,873,987 (38.4 percent) responding “no” amongst almost 80 percent of eligible voters.

In 2019, the government launched the Fourth Action Plan of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022. The plan commits to five national priorities in the quest to reduce family, domestic and sexual violence. Then, in 2020, the sex discrimination commissioner released her National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces. While agreeing in principle with or noting all 55 recommendations,

the government announced it would implement just seven of the 15 legislative reforms and rejected the recommended reform requiring employers take proactive steps to protect their employees rather than putting it on victims to initiate complaints, arguing such responsibility already existed under work health and safety laws.

Yet, as the report makes clear, such laws are not working to protect women from sexual harassment. The Sex Discrimination and Fair Work (Respect@Work) Amendment Bill 2021 is currently making its way through the legislative process.

3. Inclusive Citizenship

Average Score: 7

Indigenous Australians | Score: 7

CALD Migrants | Score: 8

Temporary Migrants | Score: 6

Australia has generally encouraged its permanent migrants to become citizens. However, changes in recent times have made it more difficult to acquire Australian citizenship, including recent reforms to temporary and permanent resident visa categories, making the pathway to citizenship less accessible. One can become an Australian citizen in one of three ways: via birth in Australia to a parent that is a citizen or permanent resident of Australia; or by descent, born to an Australian citizen overseas; or by conferral. On the latter, the following can apply to become Australian citizens:

- Australian permanent residents aged over 18,

- children aged 16 or 17,

- children 15 years or younger applying with a parent or guardian,

- Commonwealth Child Migration Scheme migrants,

- eligible New Zealand citizens,

- partners or spouses of an Australian citizen or

- refugees or humanitarian migrants.

Take-up of Australian citizenship by those eligible is high compared to other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Sixty-four percent of permanent migrants who arrived in Australia in 2011 or earlier were Australian citizens by 2016. Humanitarian migrants had the highest uptake of Australian citizenship at 78 percent, followed by skilled (67 percent) and family visa holders (53 percent).

There are several conditions that Australian permanent residents must meet to become Australian citizens by conferral. These include the following:

- Having resided in Australia for a period of at least four years, at least one year as a permanent resident;

- Not having been absent from Australia for more than 12 months in the four years preceding the lodgment of citizenship application;

- Having been residing in Australia for at least nine months in the 12 months preceding the lodgment of the citizenship application;

- Being of good moral character;

- Having passed a citizenship test in English (unless over the age of 60);

- Be likely to reside, or to continue to reside, in Australia or to maintain a close and continuing association with Australia; and

- Be in Australia when the department decides on the application (in most cases).

- While many temporary residents have no wish to stay, some temporary residents are ineligible to apply for permanent residency and thereby access citizenship.

No formal discrimination based on social identities or genders is applied to accessing citizenship. However, generally, individuals with HIV applying for permanent visas do not pass the health requirement test. While there are very high pass rates on the citizenship test and applicants can take the test an unlimited number of times, the answers to the tests are supplied in a preparation booklet and the test is not required for those with a mental or physical disability or who are under the age of 18 or over 60.There are concerns on the prohibitive nature of the citizenship test and the English language component introduced in 2007. The application process has been criticized as being marred by one’s obligation to adopt Australian values, way of life and history through the citizenship test. Critics have described the process as the return of the White Australian policy due to the inclusion of the mandatory Australian values as a knowledge to be acquired. The notion of migrants’ learning and adopting Australian cultural values has been alluded to as protecting the Australian Anglo-Celtic majoritarian values. This undermines pluralism through citizenship as inclusive citizenship means becoming a full member of the Australian community, which goes beyond mere voting for an election, to the feeling of belonging and the opportunity to fully participate in political decision-making. While permanent residency is a prerequisite to obtaining citizenship, difficult policies around the skilled, family reunion and humanitarian migration exist. It is argued that the years lived in Australia before citizenship is acquired are supposed to, in part, ensure the adaptation to the Australian way of life. During this time, based on a bad character check, visas may be cancelled—all of which undermines inclusive citizenship. There have been ongoing political attempts to make the threshold higher still.

Other current grounds for refusing citizenship include failing to pass the character test, having a criminal record and being sentenced to at least a 12-month jail term and having left Australia for a substantial period after applying for citizenship. According to a recent report, the “character test remains the blurriest area for refusing someone’s citizenship application as repeated traffic offences, and fraud charges can also be considered an indication of bad character.” An attempt to give the federal government stronger powers to cancel and refuse visas on character grounds was defeated in the Senate in 2021.

Australia allows its citizens to have multiple citizenships. The Australian Citizenship Legislation Amendment Act 2002 (Cth) permitted Australian citizens to acquire other nationalities without losing their Australian citizenship. At the same time, only citizens with multiple citizenships, and not citizens by birth, may have their citizenship revoked. This “adds another dimension of inequality … If you are only an Australian citizen, you cannot have that taken away.”

Dual or multiple citizens cannot stand for national election or sit as Members of Parliament (MPs) or senators of Parliament. This caused a political crisis in 2017 and 2018, as eight senators and seven MPs, including the deputy prime minister, were found either to hold dual citizenship (sometimes without their knowledge) or not to have fulfilled the process of renunciation correctly. The episode sparked a prolonged public debate about the relevance of Section 44 in a multicultural society and whether such a bar should be removed.

Some commentary has suggested that the bar on dual citizenship explains the low representation of ethnic diversity in Parliament. However, given the underrepresentation of even women in Parliament, the underrepresentation of ethnic diversity would appear to reflect factors other than the effect of Section 44 alone.

II. Practices

While commitments are important, pluralism requires sufficient political will and action to realize commitments in practice. This dimension includes three measures for assessing the extent to which practices of the state reflect a desire to build more inclusive and equal societies

4. Policy Implementation

Average Score: 6

Indigenous Australians | Score: 5

CALD Migrants | Score: 7

Temporary Migrants | Score: 6

The federal government supports and implements a raft of measures regarding pluralism. The state and territory governments have implemented policy commitments to immigrant pluralism seriously. At the federal level, some important multicultural policies remain active, including the public multicultural broadcaster, SBS; the Multicultural Access and Equity Policy; the Multicultural Service Officer program and Harmony Day, as well as the Aged Care Diversity Framework. The government also recently introduced significant reforms to the Adult Migrant English Program, allowing more migrants a better chance of improving their English language proficiency. Notwithstanding these initiatives, there have been notable lags in the implementation of government policies. For example, the Australian Multicultural Council, the government’s key advisory body on multicultural affairs, sat dormant for eight months after the tenure of the appointed councilors had expired.

But the lack of policy commitment and implementation concerning Indigenous communities is unequivocally clear.

The absence of equity in policy implementation among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities led them to lobby for system reform that accounts for Indigenous ways of thinking, being and doing in policies, programs and services.

This lobbying has focussed self-determination, empowerment, trust, culturally appropriate and localized solutions, holistic and decolonizing approaches, strong cultural protective factors and resilience, and respecting the voices and choices of Indigenous people. In 2005, a proposal by the then Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social justice commissioner led to the federal government’s associated Closing the Gap initiative in 2006. Over the past 15 years, there has been mixed progress in meeting the goals of Closing the Gap, with many targets unlikely to be met on time.

Noted already is the government’s rejection of the Uluru Statement as the vehicle for reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and the slow, piecemeal implementation of the ALRC’s recommendations regarding the recognition and incorporation of customary law, which reflects a failure to implement pluralism.

The record of recent federal conservative governments on gender and migrant diversity policy displays a not dissimilar reticence. The government was reticent to address the sex discrimination commissioner’s aforementioned report on Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces (2020). It took over a year for any action to be taken.

There have been five significant national parliamentary inquiries related to diversity in Australia in the last decade: Inquiry into Migration and Multiculturalism in Australia; Ways of Protecting and Strengthening Australia’s Multiculturalism and Social Inclusion; Inquiry into the Status of the Human Right to Freedom of Religion or Belief; Freedom of Speech in Australia; and Inquiry into Nationhood, National Identity and Democracy. The findings of all four inquiries have not been adequately responded to by the government, illustrating a lack of policy engagement and thus, implementation.

On citizenship acquisition, over the past several years, there have been pronounced delays in the processing of citizenship applications for some permanent resident visa holders, especially refugee and humanitarian entrants.

An unfortunate irony is that whereas recent governments have been too slow to act on Indigenous policy, diversity policy and sexual discrimination and harassment policy, they have managed to act with rapidity when it comes to reforming temporary resident visas and tightening their entitlements.

5. Data Collection

Average Score: 6

Indigenous Australians | Score: 7

CALD Migrants | Score: 6

Temporary Migrants | Score: 5

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is an independent agency that collects and analyzes data for use by Australian governments and other organizations. It collects data on population, economics, health, labour, social, industry and environmental issues. It also conducts the country’s census every five years.

There are no distinctive statistics on the inequalities for culturally diverse segments of the Australian population. Australia’s data collection on diversity is inadequate; much the same applies to group-based inequalities.

Official statistics on the composition of groups based on ethnic and cultural inequality is a difficult task. This is despite the ABS’ census collecting data that includes variables such as place of birth, language spoken at home, and identification of self-ancestry—all of which are inadequate for measuring cultural diversity in Australia. Though the ABS data are collected systematically, gaps remain in areas of diversity. For example, the Leading for Change report combined the 2016 and 2011 data regarding questions about ancestry and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people identification and showed that not only has cultural diversity increased over time but the Australian population might also be more diverse than previously reported. Additionally, significant issues about group inequalities persist in the Australian legal systems framework, notably hate or bias crimes; the severity of these crimes is usually downplayed by law enforcement agencies and in political and media discourse. Yet, robust and official data from police and law enforcement agencies necessary for intervention strategies in redressing such inequalities in the legal systems are scarce, and the data are not available for public use. Australia relies on academic institutions, community organizations, human rights agencies (e.g., the AHRC and state-based human rights and equal opportunities commissions) for data on group-based inequalities, particularly in the area of crime victimization and the protection of diverse communities. Despite this data collection, many gaps exist. Other significant organizations that collect data in Australia include the Department of Health which collects data on health. The Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey collects longitudinal data for over 17,000 Australians who are followed every year. Data on indicators such as economics, health, family life income, education, employment and labour market are collected. Other key surveys include the Australian Values Study, Building a New Life in Australia, General Social Survey (GSS) and Growing Up in Australia: A Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Social Surveys.

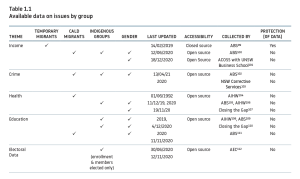

The two notable exceptions to this situation are Indigenous Australians and women (see Table 1.1). There is extensive data on Indigenous Australians’ disparate rates of morbidity, longevity, health, education, incarceration and deaths in custody, including information on the experience of Indigenous women and girls. There is also good data collected on women in Australia, including socio–demographics, health, income inequality and survey data tapping sexual harassment and family violence.

The rubric “ethno-racial communities” is not deployed in Australia; however, migrants and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (CALD) are established categories. Yet, the ABS’s regular data on the income, health, crime and education of migrants is generic, based on the recency of migration and visa status and not disaggregated by ethnic, cultural or linguistic identification. The government’s Australian Institute of Health and Welfare provides scattered data on some health and well-being indicators for migrants collectively, not disaggregated into particular communities.

Matters are better regarding cultural diversity among both older people and those suffering from mental illness. In 2013, the National Mental Health Commission funded a Mental Health in Multicultural Australia project to research and profile the needs of people suffering mental illness from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. This was followed by the current Embrace Multicultural Mental Health project. Beyond government, a cadre of academic researchers has been building an evidence-based, community-specific understanding of this special sector of the community.

The Refugee Council of Australia provides some statistical data on refugees and asylum seekers, while academic researchers are mostly relied on to fill this void.

National data gathering on temporary migrants is even sparser than that on CALD migrants and refugees. The ABS combined datasets from the 2016 census and housing and temporary visa holders’ data from the Department of Home Affairs. As the ABS notes, this initiative marks the first-ever release of such integrated microdata on temporary residents, including employment, income and housing. However, the data is far from comprehensive and can only be accessed upon application to the ABS.

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) supplies enrollment data of Indigenous Australians and maintains a list of elected Indigenous parliamentarians. It does not perform the same service for migrant communities. The AEC’s mandate does not include analyzing voting behaviour and trends nor surveying opinions on policies. Australia is poorly served in these respects, where polling and research typically focus on mainstream Christian groups. Polling organizations rarely canvas the views or political leanings of specific ethnic or faith communities. Public discussions and even academic analyses largely make do with antiquated surveys and anecdotal or impressionistic information often supplied by community insiders. Most of the work on “ethnic voting” infers dispositions from electoral results in “ethnic electorates” where at least 15 percent of the residents were born in a non-English speaking country. The dearth of ongoing reliable survey data on the country’s ethnic and religious minorities is an obstacle to evidence-based analysis of patterns and trends in the nation’s politics.

The sporadic and limited data on Australia’s CALD and temporary migrants is both anomalous and untenable given that half the current population was either born overseas or has a parent born overseas.

Until the multicultural era, post-war research in this area was almost wholly undertaken by academics. Jakubowicz observed, “Australia has a long history of using social science and historical research to help illuminate government policy in the field of immigration and cultural relations.” Australia’s multiculturalism turn led to the establishment of a new research institute, the Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs, in 1979. The Institute commissioned and conducted research and created “a repository of literature and other material” on diversity but was abolished 10 years later. Others followed with even shorter periods of operation. The dearth of relevant data and research was noted by a parliamentary inquiry in 2013, which was rejected in 2017 by the government dismissing the need for establishing an independent research body and instead touting the ability of “government departments and agencies to collect, analyze and share data on the cultural and linguistic diversity of their client base’ in conjunction with academic researchers.”

As a result, Australia’s research capacity on cultural diversity has been limited. Castles et al. contended that “[t]he demolition of Australia’s independent research capacity has led to a severe deficit in the capacity to analyze existing transformations and future trends.” Similarly, a 2018 report by the AHRC noted that Australia does not collect comprehensive data on cultural diversity.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the problems of poor research. As cases spiked in 2020, “it was revealed that even Australia’s National Notifiable Diseases database lacked data on the ethnicity, language spoken, and country of birth of Australian residents.”

6. Claims-Making and Contestation

Average Score: 5

Indigenous Australians | Score: 5

CALD Migrants | Score: 6

Temporary Migrants | Score: 4

Australia has a robust democratic culture. Claims-making is normatively accepted, even routine, and there are celebrated national examples predating federation, such as the women’s suffrage movement in the late nineteenth century, that continue to reverberate in the national imagination. Australians do not fear repression or punitive action by the state in prosecuting their claims. Civilian demonstrations and public protests are permitted, though they typically require permits and that they remain orderly. Petitioning the government and approaching one’s local MP are also commonplace.

The Scanlon Foundation’s annual Mapping Social Cohesion Survey found that, within the last three or so years, 55 percent of respondents had signed a petition, 28 percent had posted something about politics online, 21 percent had attended a political or problem orientated meeting, 20 percent had written or spoken to a federal or state MP, and 18 percent had joined a boycott.

Various legal, quasi-legal and formal institutions exist to facilitate claims-making. For example, the AHRC is empowered to pursue complaints received by individuals in regard to discrimination, harassment and bullying on grounds including the following:

- sex, including pregnancy, marital or relationship status including same-sex and de facto status, breastfeeding, family responsibilities, sexual harassment, gender identity, intersex status and sexual orientation;

- disability, including temporary and permanent disabilities; physical, intellectual, sensory, psychiatric disabilities, diseases or illnesses; medical conditions; work related injuries; past, present and future disabilities; and association with a person with a disability;

- race, including colour, descent, national or ethnic origin, immigrant status and racial hatred; and

- age, covering young people and older people.

The Fair Work Commission, which administers the provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), adjudicates claims relating to employment conditions. The Fair Work Ombudsman provides a source of information and advice to individuals, businesses and employers about workplace rights and obligations. In recent years, a number of businesses and industries have been exposed and penalized for violating fair work conditions for temporary migrants. Most sizeable firms and businesses provide recourse to “in-house” complaints mechanisms and protocols.

Temporary migrants experience a range of difficulties directly related to their visa status. For those who arrive to fill employer sponsored positions, the loss of sponsorship can mean having to depart the country. This precariousness inherently increases the leverage employers have over these workers and greatly reduces the latter’s bargaining power regarding work schedules and conditions and allowance for their cultural commitments, even where the employers’ demands may be illegal.

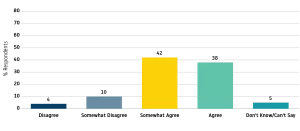

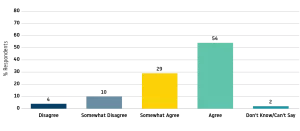

In Australia, there is evidence of the strategic long-standing shrinking of civil society associations including unions, religious and not-for-profit organizations due to strategies designed to block advocacy and to encourage these organizations to undertake service delivery instead. This, in turn, has implications for limits on gathering spaces that would otherwise foster discussion, interpretation and actions on political lives; thus, making it difficult for people to fully participate in democracy. In 2014, the Scanlon Foundation surveys highlighted Australians ambivalence about democracy. This is reflected in the most recent survey by the Global Centre for Pluralism’s (the Centre) Pluralism Perceptions Survey where only about 38 percent of participants believed that democracy works well in Australia, shown in Figure 1.1. The composition of this Australian data was comprised of participants who identified as Australians, Europeans and Americans (70 percent), Asians (12 percent), Oceanian and Sub-Saharan African (2 percent), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (1 percent). Those who identified themselves as Other or “declined to say” made up 14 percent. As such, the interpretation must be taken into consideration throughout this report.

In a diverse society such as Australia, solidarity across differences promotes unity and fosters success in seeking justice through contestation. However, studies have shown that the real justice needed to make claims and engage in peaceful contestation in Australia can never be achieved without justice for Indigenous peoples. Such justice may give rise to the assembly for good political discourse which may enhance participation in claims-making among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This would encourage fair decision-making processes and the affirmation of participation, unity and collaboration. Furthermore,

there is evidence that advocacy and lobby groups for people of colour and those experiencing discrimination from organizations such as the AHRC and the Asian Australian Alliance have limited teams and resources to carry out their duties.

III. Leadership for Pluralism

Pluralism requires leadership from all sectors in society, including non-state actors that may adopt policies and practices that affect groups’ ability to fully participate in society. This indicator assesses four critical non-state actors.

7. Political Parties

Average Score: 5

Indigenous Australians | Score: 6

CALD Migrants | Score: 5

Temporary Migrants | Score: 3

There are notable differences between the three main parties in their espousal of pluralistic values.

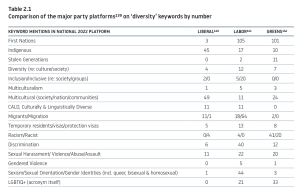

Table 2.1 below compares the Liberal, Labor, and Greens parties on the extent to which 16 “diversity” keywords or word-clusters appear in their official party platforms for the 2022 election.

All three parties address Indigenous issues to a considerable extent. In doing so, the Liberals refer to “Indigenous” communities and issues, while both Labor and the Greens overwhelmingly refer to “First Nations” peoples, signaling a more thoroughgoing recognition. The Greens make a point of keeping justice for the Stolen Generations in sight.

Of the three parties, Labor (ALP) is the most encompassing and supportive of social and cultural pluralism, addressing all 16 diversity themes in its platform statement. Significantly, it uses the language of inclusion and inclusiveness far more than the other two parties (the Greens do not use these terms at all). It also refers more to diversity, migrants and migration, temporary residents and or temporary visas, and to multiculturalism, though, on the latter, the frequencies are low and the difference to the Greens is marginal. The ALP platform states that it is the “party for, and of, multiculturalism.” The Greens, however, are the only party of the three to commit to enshrining multiculturalism principles in a legislative Act.

The Liberals’ single reference to “multiculturalism” occurs in reporting a survey’s findings. They richly deploy the adjective “multicultural” (much more so than Labor and the Greens), however, this does not indicate commensurate support for affirmative multicultural programs. The Liberals’ platform promises to increase funding for the multicultural broadcaster, SBS, and to provide some modest assistance for community newspapers facing rising costs. It also commits to protecting the rights of faith communities (the rights of other cultural communities go unmentioned). Otherwise, the emphasis is on commonality rather than diversity: policies and programs that foster social cohesion and “strengthen communities” by assisting migrants to integrate and acculturate to Australia.

Interestingly, both Labor and the Liberals refer to “CALD” groups some eleven times, whereas the Greens do not use this category.

Another contrast concerns the treatment of prejudice, with the Greens emphasizing racism and Labor, discrimination. The Liberals are comparatively light on both. Labor and the Greens are also strongly attentive to sexual harassment and sexual violence against women and equality for LGBTIQ+.

Representation of diversity within the parties’ own ranks is also wanting, even if, in the case of women, Australia performs better than the legislatures in Canada, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US). In the current (47th) Parliament, 46.8 percent of the federal lower house’s ALP MPs are female, compared with the Liberals’ 21.4 percent and the Nationals’ 14.2 percent (2 of 14 members). Nine of the ten Independents are women. In the Senate (federal upper house), the ALP, the Nationals and the Greens each have majority female representation (ranging from 66.7 to 69.2 percent); the Liberals have 38.5 percent. In the 2022 election, Labor and Liberal women candidates were again disproportionately placed to contest marginal rather than safe ALP or Liberal seats.

As of September 2022, total female representation by party across all parliaments – federal, states and territories (including both chambers as applicable) – has the Greens highest with 59 percent, the ALP averages 48.4 percent, the Liberals 30 percent, and the Nationals with 28.3 percent.

There have been sixteen Indigenous federal parliamentarians in the history of the Commonwealth, five of whom entered Parliament in the 2022 general election. Of the sixteen, nine were elected as Labor members, three as Liberals (one of whom defected to be an Independent), one as an Independent, and one each representing the Australian Democrats, Country Liberal Party, and the Greens. Ten of the sixteen Indigenous parliamentarians have been women. Eleven were elected on Senate tickets. The first Indigenous member of the House of Representatives (Ken Wyatt, LIB, who served as Minister for Indigenous Australians), was elected in 2010, while the first Indigenous female member of the House of Representatives (Linda Burney, ALP), was elected in 2016. There are currently a record eleven Indigenous parliamentarians at the national level. With eight Indigenous Senators in a chamber of 76 Senators, there is for the first time a modest overrepresentation of Indigenous Australians in the Senate (10.5 percent to 3.2 percent in the overall population), and even a small overrepresentation in the Parliament overall (4.9 percent of the 227 members and senators).

The current ethnic profile of the parties is not readily accessible.

In the 45th Parliament elected in 2016, fewer than 20 of the then 226 federal parliamentarians had a non-English speaking background, and little changed following the 2019 election. The underrepresentation is particularly pronounced in the case of Australians with Asian backgrounds. An AHRC report in 2018 found that only 4 percent of federal MPs (excluding the ministry) were of non-European ancestry although the latter constituted 19 percent of the Australian population. Of the 30 members of the ministry, 83.4 percent had an Anglo-Celtic background, another 13.3 percent had a European background, while there was one Indigenous member and no others were of non-European background. In the 2019 election, only three candidates with Asian ancestry were elected to the 151-seat House of Representatives (i.e., some 2 percent of the chamber that forms government). Among the three was the first Chinese-Australian woman elected to the federal lower house.

The current (47th) parliament elected in 2022 marks some progress. Whereas in the previous two parliaments only around 4 percent of all parliamentarians came from a non-European or Indigenous background, the current parliament saw that figure jump to 10 percent.

However, this still grossly underrepresents the estimated 24 percent of people from such backgrounds in the Australian population.

The Albanese government also achieves some milestones in minorities assuming cabinet posts, with the first Foreign Minister who is Asian-Australian (Penny Wong), the first First Nations woman to be Minister for Indigenous Affairs (Linda Burney), and the first female Minister who is Muslim with Dr Anne Aly leading the Early Childhood Education and Youth portfolios.

On the positive side, also, there has been increasing public attention devoted to the lack of diversity in the nation’s legislatures. A 2019 poll found that 71 percent of Australians wanted a more diverse Parliament. And a number of current state party and recent minor party leaders have come from non-English speaking backgrounds.

A discussion of parties and pluralism in Australia must also address the power of minor parties to impact Australian politics and broader public discourse. For example, the One Nation Party has, for nearly 25 years, expounded xenophobic, anti-Asian, anti-multiculturalism and anti-politics politics.

Minority communities continue to raise concerns about the behaviour of major (right-wing) political parties. For example, the recent “African gangs controversy”, fueled by Liberal Party political rhetoric, was divisive and undermined political leadership for pluralism. The Home Affairs Minister at the time, Peter Dutton, suggested that Victorians were too scared to go out to restaurants in the wake of incidents involving some individuals of South Sudanese background. This stereotyping has further been highlighted by various academics and human rights organizations who continue to emphasize how culturally diverse community individuals are represented as victims of the Australian system and often portrayed as a threat to the Anglo-Australian way of life. As such, major political parties’ engagement with the Australian media has been shown to undermine or suppress pluralism. For the political parties to espouse the values of pluralism, the actors of major political parties must aspire to use the media to balance news that reflects the diversity of Australian multicultural communities. News coverage should not be skewed towards the perceptions of white Australians as is currently the case.

8. News Media

Average Score: 4.5

A. Representation | Score: 4

Indigenous Australians | Score: 4

CALD Migrants | Score: 5

Temporary Migrants | Score: 3

B. Prominence of Pluralistic Actors | Score: 5

Indigenous Australians | Score: 6

CALD Migrants | Score: 6

Temporary Migrants | Score: 3

In practice, the obvious lack of diversity promotes negative media narratives and discourses to continue to convey a picture of exclusiveness. The lack of diversity in Australian journalism (meaning language, gender, ethnicity and age) is a contributing factor.

A marked factor undermining pluralism is the one-sided workforce and leadership positions which are largely culturally monolithic in their whiteness.

This is because the Australian media is largely represented by middle-aged white men, and the composition of the leadership is overwhelmingly individuals from Anglo-Celtic backgrounds.

The public multicultural SBS, which spans television, radio and online services, is one of the enduring legacies of early multiculturalism policy and leads the advance of media diversity nationally. In addition to its English-language broadcasting, SBS offers news and entertainment in many languages. Today, it draws audiences from across the nation’s population. In recent years, the national public broadcaster, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), has increased minority ethnic representation among its newsreaders and public-facing personnel.

In contrast, commercial media outlets do not represent diversity well. A three-year study of diversity in the Australian media conducted by Media Diversity Australia with researchers from four Australian universities, found the following:

- At all networks other than SBS (where 76.6 percent of presenters, commentators and reporters have a non-European background), people with non-European backgrounds comprise less than 10 percent of presenters, commentators and reporters; and on commercial networks, they count for less than 5 percent, despite constituting 21 percent of the Australian population.

- No Indigenous presenters, commentators or reporters were identified at Channel 7, a commercial network, and there was only one each at Channel 9 and 10. Even at SBS, Indigenous presenters, commentators or reporters comprised only 0.2 percent of the sample.

- One hundred percent of free-to-air television national news directors have an Anglo-Celtic background and are all male.

- Board members of Australian free-to-air television are also overwhelmingly Anglo-Celtic. Of the 39 directors, there is only one who has an Indigenous background and three who have non-European backgrounds.

- In a survey completed by more than 300 television journalists, more than 70 percent of participants rated the representation of culturally diverse people in the media industry as either poor or very poor.

- Seventy-seven percent of respondents with culturally diverse backgrounds believe their heritage is a barrier to career progression.

Similarly, a Screen Australia inquiry reported a pronounced underrepresentation of non-Anglo-Celtic Australians in locally made TV drama.

Australia’s media landscape is divided. There is a multitude of ethnic community newspapers and broadcast media that reflects the country’s diverse society, but the mainstream media does not. A recent report on Australian news media arguably identifies part of the problem:

“Australia’s nearly unrivalled concentration of media ownership has historically worked and continues to work against a pluralistic media environment.”

Such structural factors are, however, aided and abetted by ingrained cultural predilections. These require addressing much more forthrightly by all parties concerned, not least by policy-makers in government and by media organizations.

The heavy lifting in support of Australian diversity among news media actors is mainly done by media bodies through their publications, editorials and programming. The two public broadcasters, SBS, as the multicultural broadcaster, and, more controversially, ABC (given its charter commitment to political neutrality), are strong defenders of diversity in the community (even if they sometimes fall short in their own staffing). Both main metropolitan dailies, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age (Melbourne), along with The Guardian (Australia), provide centre and centre-left commentary and editorial support in defense of diversity values. For many years, The Australian (part of the Murdoch newspaper stable) has taken a keen and supportive interest in Indigenous affairs. The Saturday Paper, The Monthly and the Quarterly Essay from the Black Inc. stable in Melbourne, and New Matilda provide more boutique avenues for critical leftist commentary and support for multicultural Australia. The Conversation, Australian Review of Public Affairs and On Line Opinion are open fora that invite a wider canvassing of views, though tend to be pro-diversity and pluralism overall. More specialist media outlets (though not news) include Arena and Arena Magazine, Griffith Review and Australian Book Review.

At the individual level, a dozen or so prominent media actors routinely promote and defend Australia as an inclusive and pluralistic society. They include broadcasters and columnists Phillip Adams and Waleed Aly; Indigenous journalist Stan Grant; journalist David Marr; academic, broadcaster and newspaper commentator, and contributing editor to The Australian Peter van Onselen; author, journalist, radio and television presenter (and chair of the Republic Movement) Peter FitzSimons; former race discrimination commissioner, now academic and occasional newspaper columnist Tim Soutphommasane; ABC senior producer Rachael Kohn; ABC presenter Virginia Triolli; feminist commentator Eva Cox; academic Catharine Lumby; editor of ABC’s Ethics and Religion website Scott Stephens; journalist and broadcast compere Julia Baird; satirists Juice Media; comedian Shaun Micallef; and, before he lost his voice to cancer, politics professor Robert Manne, long named as Australia’s best-known public intellectual. The brevity of this list is in contrast with the legion of prominent conservative and libertarian critics of multiculturalism and “identity politics” in Australian media.

Consequently,

the lack of diversification in the media systematically undermines pluralism through exclusionary negative narrations and discourses.

As such, views from the news media outlets are not representative of the general population and are usually interpreted as prejudiced and discriminatory against minority groups. This is evident in a report that analyzed 315 opinion pieces of negative representations of communities in major Australian News Corp publications. Of them, 90 percent of news stories from The Herald Sun were negative, the highest, from The Daily Telegraph (80 percent) and The Australian (52 percent). Of the targeted community with the highest percentages of negative representations, 75 percent were Muslims, 55 percent were Chinese and Chinese-Australian people, and 47 percent were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Unless prominent media actors, including major political parties, use their influence to counter negative, divisive and hierarchical depictions of minority groups, pluralism in Australia cannot be achieved. The outcome of these media outlets’ representations of minorities has negative implications for cultural diversity and social cohesion in Australian society.

9. Civil Society

Average Score: 7

Indigenous Australians | Score: 7

CALD Migrants | Score: 7

Temporary Migrants | Score: 7

Australia has been estimated to have over 300,000 non-government and non-profit organizations, many of which espouse pluralism. Prominent ones include the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS); Refugee Council of Australia; Amnesty International; the Federation of Ethnic Communities Councils of Australia (FECCA), along with its various state bodies; the Scanlon Foundation; Get Up!; Diversity Council Australia; and two think tanks, the Australia Institute and the Lowy Institute. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), the Lowitja Institute and the Aboriginal Advancement League promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ interest, while the FECCA and Refugee Council of Australia represent and advocate for migrants and refugees. Others include the Migration Institute of Australia, which provides welfare services to mainly minority groups in Australia and internationally. There are organizations, such as The Salvation Army and ACOSS, that advocate for inequalities to be addressed, particularly in disadvantaged and poverty-stricken areas, as well as All Together Now, whose work includes destabilizing far-right extremism and combating racism in Australia. Most of these organizations, including the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Human Rights Commission, the ACT LGBTIQ Advisory Council and the Australian Christian Lobby made significant submissions to the review of the Racial Discrimination Act.

Other significant bodies working in this space include the Australian Communities Foundation, Minderoo Foundation, Centre for Cultural Diversity in Ageing, Centre for Multicultural Youth, Australian Fabians, Evatt Foundation, Centre for Policy Development, McKell Institute, Per Capita, Whitlam Institute, Centre for Australian Progress and the Queensland-focused Multicultural Australia and the Australian Multicultural Foundation.

These civil society actors provide vital linkages between stakeholder communities and federal, state/territory and local governments, often conveying sets of interests and concerns about which government bodies might otherwise lack awareness.

There are also a number of impactful university-based research centres and advocacy institutes, including the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University; Monash Migration and Inclusion Centre, Monash University; Migration and Mobility Research Network, University of Melbourne; Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University; Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, UNSW; Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, UNSW; Centre for Social Justice and Inclusion, University of Technology Sydney; Sydney Institute for Community Languages Education, University of Sydney; and Centre for Research in Educational and Social Inclusion, University of South Australia.

10. Private Sector

Average Score: 7

Indigenous Australians | Score: 7

CALD Migrants | Score: 7

Temporary Migrants | Score: 6

Over the past decade, Australia has enjoyed a strong sustained economy and productivity due, in part, to a competitive and diverse workforce comprised of people of different religions, races, ages, genders and abilities, and cultural backgrounds. The role of workforce sectors and leadership in aiding pluralism in Australia is far-reaching.

Gender diversity in the Australian workforce and in company leadership remains inequitable. The ratio of women to men in the Australian labour force (based on the percentage of the total population ages 15 and over) is 0.83. Though women represent 40 percent of those employed at Australian companies, their underrepresentation in the executive team and board of directors of companies is more pronounced at 21 percent and 30 percent, respectively.

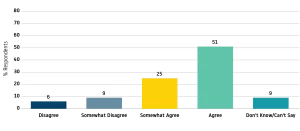

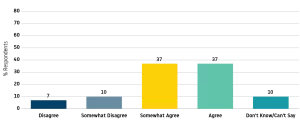

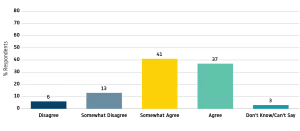

Ethnic minorities are underrepresented in leadership positions, both in private sectors and governmental positions. This is due to conscious and unconscious bias in selection and promotion to leadership positions by the largely dominant white male groups. Ethnic minorities face the prospects of not being selected or promoted into a management position. Other factors that affect minority groups in leadership positions in Australia include lack of recognition of credentials, limited local work experience, and reduced English language skills. In the Centre’s Pluralism Perceptions Survey, less than half the participants agree that they are equally likely to be hired and promoted for a professional role as other Australians shown in Figures 2.1 and 2.2.

An AHRC report on cultural diversity within Australian leadership positions found a stark underrepresentation of people with non-European and Indigenous backgrounds in the leadership of ASX 200 companies. Of the 200 CEOs of these companies, 72.5 percent have an Anglo-Celtic background (compared to 58 percent of the Australian population), 23.5 percent have a European background (compared to 18 percent of the population), 4 percent have a non-European background (compared to 21 percent), and none have Indigenous heritage (compared to 3.3 percent of the Australian population). Similarly of the 1,463 non-CEO executives serving in ASX 200 companies, Anglo-Celtic backgrounds still dominated at 73.2 percent, with European backgrounds comprising 21 percent and those with non-European backgrounds comprising 5.8 percent of these positions.

Surveys suggest that Australians overwhelmingly support ethnic diversity in the workplace.

The AHRC reports found that many of Australia’s largest companies have introduced policies designed to increase diversity in their workplaces. There is a tradition of private companies sponsoring sporting teams, community festivals and the arts. For example, former CEO and non-executive chair of Fortescue Metals Group, Andrew Forrest, has sponsored apprenticeship schemes for Indigenous youth. Prominent tax lawyer Mark Leibler has been heavily involved in promoting the cause of reconciliation. Suncorp Bank, the Australian Football League (Queensland), Brisbane Lions Football Club and Brisbane Roar Football Club are all partners of Multicultural Australia. Qantas, the national airline, has promoted itself as a unifying symbol of a multicultural Australia. Former long-time chair of Westfield Corporation Sir Frank Lowy has been a vocal defender of Australian multiculturalism. Atlassian co-founder and co-CEO Mike Cannon-Brookes has been a very public face advocating for diversity both within and beyond his company.

There are also some notable failures of leadership on diversity. The National Rugby League football code has struggled with sexism, harassment and sexual violence within its ranks in recent years, while the Australian Football League (Australian Rules) has been found wanting in its response to internal and crowd expressions of racism.

IV. Group-based Inequalities

Around the world, inequalities and exclusions strongly correlate with markers of group difference. In this section the Monitor assesses the breadth of inequalities, their durability and the overall difference in treatment between groups.

11. Political

Average Score: 4

Indigenous Australians | Score: 5

CALD Migrants | Score: 6

Temporary Migrants | Score: 2

Opportunities for political participation are generally equitable for citizens; however, there are some areas of qualification, concern and debate. In Australia, equitable political representation and participation among its citizens are still far from being achieved. As noted above, there are legal restrictions, such as the constitutional bar on dual citizens being candidates in federal elections. Also noted above is the underrepresentation of women and cultural minorities in Parliament (see Indicator 3).

All citizens are able to vote but not permanent and temporary migrants. Permanent and temporary migrants can politically associate, express their political views, whether in letters to politicians or newspapers, writing an article for a newspaper, being interviewed on radio or television or through protest. But the denial of the franchise raises genuine issues about how the interests of these classes of migrants might be politically represented.

The two main left-leaning political parties do not bar temporary residents from becoming members. The ALP requires members have an Australian residential address, while the Australian Greens do not require even that for membership. In contrast, only Australian citizens are eligible for membership in the two main conservative parties.

Furthermore, pluralism will not be achieved in Australia until minority communities including the LGBTQI+ community, people with a disability, those who are homeless, in poverty, unemployed, casual workers and small business owners facing challenges are considered as citizens and partners in finding solutions within the political sphere, not as clients or consumers, or vulnerable people who need protection. Democratic and political participation among ethnic communities should go beyond voting in elections, and political discourses must not function on an exclusionary basis based on race, religion and country of birth. This will enhance equitable political representation in Australia. Figure 3.1 provides evidence, from the Centre’s Pluralism Perceptions Survey, on participants’ views, with approximately 35 percent believing their views are being represented by political parties.

Historically, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were excluded in the drafting of the Constitution. To an extent, the Australian Constitution still allows for racial discrimination of not only Indigenous Australians but also against other minority groups. This has been reflected in the Australian political inequalities contributing to a lack of representation and participation of diverse communities in the political arena. As such, there is a lack of minority voices in political representation. For equitable and diverse political representation to be achieved, the denial of the Indigenous political voice and Indigenous input in policy that directly affects them must be addressed. Adopting the recommendations of the Uluru Statement is a necessary first step in achieving equitable political representation, namely constitutional enshrinement of a Voice to Parliament as a permanent institution for expressing Indigenous views to Parliament and to government on important issues affecting Indigenous peoples. This should be combined with a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and Indigenous peoples that provides a clear and practical path forward for Indigenous self-determination in accordance with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The minimum age restriction is also contested. For most of the last century, the minimum age for voting in federal elections was 21 years. In 1973, the age was lowered to 18 years, where it remains. But there have been attempts to lower the age to 16 years by the Greens.

Prisoner disenfranchisement in Australia is another issue. Prisoners serving full-time sentences of more than three years are ineligible to vote in federal elections. There are different provisions in some states; with some penalizing prisoners with sentences of more than five years, others doing so for those with one-year sentences. Beyond the citizenship rights of prisoners, such disenfranchisement can also have “a disproportionate impact on groups who are overrepresented in the prison population, such as Indigenous peoples, people with a mental illness and people with an intellectual disability.”

Another debate is the status of Australia’s compulsory voting laws: Do they enhance political equality or violate it?

12. Economic

Average Score: 5

Indigenous Australians | Score: 4

CALD Migrants | Score: 6

Temporary Migrants | Score: 4

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples there continues to be a long-standing history of economic inequalities. This is attributable to the effect of historical laws that continues to deny Indigenous Peoples equitable participation and access in the economic domains. Even where jobs are secured, institutional racism coupled with a culturally unsafe working environment contributes significantly to the lack of participation in the economic domain in Australia. The role of institutional racism in inequitable access to the economic domain is marked in Australian society. Institutional racism has resulted in reduced recruitment and retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander professionals. This contributes not only to low income and wealth but also increases the wage gap between the Indigenous Peoples and the non-Indigenous population. The deficit in access to public and private sector employment among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples has been reflected in the Close the Gap initiative. In the report, culturally appropriate, sensitive and safe working environments (e.g., health systems) were recommended for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a significant and integral part of their employment. This equitable working system should acknowledge institutional racism and put in place steps, through culturally safe training, to close the gap and to ensure wealth, income and wages are proportionate to all.

Gender-based economic inequality also persists in Australia. According to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA, 2020), women earn, on average, $25,534 (AUS) per annum (p.a.) less than men and face a 20 percent gap in total wages, which also impacts retirement savings. Other findings include the following:

- The national gender pay gap is 13.4 percent (a gendered difference of $15,144 (AUS) p.a.).

- Nationally, women continue to dominate part-time and casual roles; only 38.1 percent of full-time workers are female.

There is, however, strong growth in flexible working opportunities, evidence of a rise in the number of women to managerial level and improved access to parental leave.

There are significant income disparities between migrants from non-English-speaking countries and the Australian-born and migrants from English-speaking countries. Those born in Australia or other English-speaking countries are more likely to be in the top 20 percent income group, whereas people born in non-English speaking countries are more likely to be in the lowest 20 percent income group.

Access to public and private-sector employment

A suite of protections against discrimination in employment apply at federal and the state and territory levels (see Section 2). Federally, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), prohibits unfavourable treatment in employment because of race, colour, ethnicity or national origin. Nevertheless, access to employment opportunities is not always equitable: evidenced by the underrepresentation of women in full-time employment and leadership roles and of people from Indigenous and non-European backgrounds in public sector roles (parliamentarians, government ministry, government departmental secretaries and deputy secretaries or equivalents at the federal and state levels), among university chiefs and in the private sector at the managerial level (ASX200 CEOs and non-chief executive leaders), outlined in Sections 10 and 11.