Country Report

Évaluation Nationale du Moniteur: Canada

Le pluralisme varie selon les minorités au Canada. Les expériences des groupes minoritaires montrent qu'il reste encore beaucoup à faire.

Overall Score: 7

This assessment was completed in 2021.

Canada is known internationally as a multicultural country, and many Canadians see pluralism as a central part of the cultural and national identity of the country. However, the Global Pluralism Monitor: Canada report tells a more complicated story, in particular about the experiences of Quebec as a sub-state nation, ethno-racialized minorities (particularly recent immigrants), and Indigenous Peoples.

Two major threads run through this report. The first highlights how the extent to which pluralism has been realized varies across the 20 indicators in the Monitor’s assessment framework. The accommodation of pluralism is much stronger in some domains than others. The second thread highlights the dramatic differences across different minorities and Indigenous Peoples in Canada, with some minorities enjoying much stronger protections than others.

I. Commitments

For pluralism, legal commitments are the most prominent way for states to declare their intent to build inclusive societies, and for non-state actors to keep states accountable. Legal commitments to pluralism can anchor other efforts to make society’s hardware and software more inclusive.

1. International Commitments

Average Score: 6.5

Québécois | Score: Not Applicable

Ethnoracialized Minorities | Score: 8

Indigenous Peoples | Score: 5

International law is an important starting point for pluralism. Canada has ratified 10 major United Nations (UN) human rights treaties and consistently submits periodic reports addressing treaty implementation. But Canada has declined to ratify the treaties related to human rights and pluralism developed by the Organization of American States (OAS).

Table 1.1 Treaties on human rights and pluralism ratified by Canada

Québécois

Canada’s international commitments apply unevenly across different types of minority groups. Such commitments have little relevance to the Québécois national minority. The UN did adopt a Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities in 1992. Although the declaration was adopted by the UN General Assembly without a formal vote, Canada probably supported the document in spirit. However, as a “declaration,” the commitment does not involve the level of monitoring and accountability associated with conventions (i.e., no annual reports, no complaints procedure). Indeed, the UN minorities declaration is so weak and vague that Québécois would have no reason to ever invoke it. Their national constitutional guarantees are much stronger than what the UN Declaration provides.

Ethnoracialized Minorities

International commitments do inform debates about other minorities, and Canada is actively involved in the monitoring mechanisms of the treaties to which it is a party.

Various committees on the implementation of UN treaties have noted positive steps that federal and provincial governments have taken to implement treaties. These include the development of an anti-racism strategy in Ontario and the condemnation of Islamophobia by the federal House of Commons. Also noted are measures to protect economic, social and cultural rights by restoring access to the interim federal health program to refugees and making diversity a priority in appointing federal Cabinet ministers.

However, committees have also noted a wide range of concerns, including the following, for example:

- In 2012, the Committee on the Rights of the Child emphasized the overrepresentation of black and Indigenous children in the criminal justice system and among children who had been removed from their homes.

- In 2015, the Human Rights Committee raised numerous concerns about counterterrorism measures and rights compliance, including due process failures for the deportation of non-citizens under the security certificate regime. In 2018, concerns about Canada’s security certificate regime were again raised by the Committee against Torture, which emphasized the potential for indefinite detainment of suspected terrorists and the limited capacity of special advocates to seek evidence on behalf of those named in security certificates.

- In 2016, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights highlighted the continued failure to protect socio¬–economic rights in domestic courts or deem them justiciable. The Committee lamented the lack of legal remedies to address Covenant violations and the disproportionate impact of this omission on Indigenous and racialized persons. The plight of seasonal agricultural workers was also addressed, stating that Canada’s permit system, which ties temporary and seasonal migrant workers to a specific employer, creates the risk of exploitation. Recommendations here included increased inspections and replacing employer-specific work permits with “type-of-work” permits to help promote more just working conditions.

- In 2017, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination noted Canada’s failure to provide disaggregated economic and social data to evaluate the enjoyment of rights by specific racialized, Indigenous and non-citizen groups. These diverse communities were effectively rendered invisible by use of the term “visible minority.” Discrimination and inequality in education and employment affecting Indigenous and racialized persons were also raised.

- In 2018, the Committee against Torture raised concerns about the operation of the Safe Third Country Agreement and recommended that Canada undertake an assessment of the agreement’s impact on asylum seekers who fear deportation and have compelling grounds for refugee status.

Indigenous Peoples

In addition to the reports above, which deal generally with racialized and Indigenous communities, a number of reports have focussed explicitly on the treatment of Indigenous Peoples, where Canada’s record is weaker. Several of the concerns of treaty monitoring bodies speak specifically to the treatment of Indigenous Peoples.

- In 2012, the Committee on the Rights of the Child noted Canada’s failure to address disparities between child welfare services for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children, despite a finding of inequality by Canada’s auditor general, as well as concern for the ability of children removed from their homes to preserve their cultural identities.

- In 2015, the Human Rights Committee expressed concerns about the disproportionate incarceration rates of Indigenous Peoples and protracted land claim disputes. Meeting basic sustenance needs and the continuation of Indigenous languages were also raised.

- In 2017, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination raised concerns with respect to Indigenous rights regarding resource development and the underfunding of child and family services for Indigenous children.

- In 2018, the Committee against Torture addressed the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), recommending that all justice officials and law enforcement personnel receive mandatory training on the prosecution of gender-based violence. The Committee also called on Canada to investigate and prosecute all gender-based violence against Indigenous women and girls, including violence perpetrated by state authorities, and to provide a mechanism for the independent review of cases where allegations of incomplete or inadequate police investigations are made. The Committee further urged Canada to accede to the International Convention of the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Interference and to track the number of complaints, investigations, prosecutions, convictions and sentences involving gender-based violence, using disaggregated data that includes the age and ethnicity or nationality of the victim.

Canada’s slow accession to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) deserves particular discussion. Canada actively lobbied against the agreement in 2006 and 2007. It voted against UNDRIP in 2007 before endorsing it with the reservation that it did nothing to change Canadian law, signaling an unwillingness to implement or even be bound by many of the provisions in the declaration. Following a change in government from the Conservative Party to the Liberals in 2015, Canada accepted the declaration in full in 2016. However, the government pre-emptively stated that the declaration will not affect case law of the Supreme Court of Canada on Canada’s fiduciary duty/duty to consult.

Progress on the implementation of UNDRIP has been slow. As of 2019, both the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and the Inuit Tapiritt Kanatami had raised concerns about the lack of UNDRIP’s implementation. Implementing UNDRIP will require Canada to grapple with significant issues. This includes the disproportionate level of violence directed against Indigenous women and girls, which was the subject of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The agenda also includes resolving the conflict between both governments and industry and Indigenous nations over the development of resource extraction related projects, such as the Trans Mountain Pipeline and the Coastal GasLink pipelines that run through different nations’ territories. Other issues include non-compliance with orders of the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal over the provision of equitable social services to Indigenous children.

While there is a certainly a symbolic commitment to UNDRIP on the part of the federal government, it is unclear what the commitment means for conflicts between Indigenous nations and the federal government, or for the social and economic inequalities experienced by Indigenous nations. In December 2020, the federal government introduced legislation on implementing UNDRIP. However, the legislation stops short of giving Indigenous nations a veto over projects such as natural resource development on their traditional territories, insisting that the existing Canadian constitutional structure allows the federal government the final decision over projects deemed to be of public interest.

2. National Commitments

Average Score: 6.5

Québécois | Score: 9

Ethno-racialized minorities | Score: 7

Indigenous Peoples | Score: 4

National legal commitments serve as the formal basis for the state’s response to diversity. Once again, the legal and policy frameworks that recognize and protect the rights of groups differ across minority groups and Indigenous Peoples.

Québécois

The federal system, with its decentralized and asymmetric features, provides French speakers in Québec with a powerful instrument of self-governance. The division of powers in the federation is comparatively decentralized and asymmetric arrangements have enhanced the powers of the Province of Québec over culturally sensitive policies including immigration. The rights of Québécois are also anchored in the Canadian Constitution. Sections 16–20 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter) (1982) entrench French as an official language of Canada, and s. 23 protects minority education rights, allowing French-speaking citizens in English majority provinces to school their children in French. Finally, s. 93 (1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 safeguards the status of publicly funded denominational schools that existed at Confederation, protecting them from the provincial power to legislate in the area of education.

The right of Québec to self-determination is further protected by the Québec secession reference case brought before the Supreme Court following the 1995 referendum on Québec sovereignty. In the reference case, the Court found that, while Québec did not have a unilateral right to secede, the federal government and provinces would be expected to negotiate the secession of Québec in good faith in the event that a clear majority of Quebecers voted in favour of secession on a clear question. In the aftermath of the judicial reference case, the federal government passed the Clarity Act (2000), which allows the federal government to stipulate what they would recognize as a clear majority and a clear question. This places some constraint on the ability of Québec to vote for its secession from Canada, though it is unlikely that the federal government would be able to prevent Québec from seceding unless a vote for secession was decided by a very narrow margin.

Québec’s distinct national identity has been formally recognized twice by resolutions in the federal Parliament.

This was done in 1995 shortly after a referendum on Québec sovereignty failed by a razor-thin margin. Québec was also recognized as a “nation within Canada” in 2006, as the government sought to deflect a resolution moved by the Bloc Québécois (a Québec separatist party) that would have recognized Québec as a nation without the stipulation that it was a nation within Canada. Both resolutions have been treated largely as symbolic and came in response to efforts by sovereigntists to assert a greater degree of independence for Québec.

In addition to this broad recognition, the rights of Québécois are defined in specific policy domains through legislation of the federal government and the provincial government of Québec. In some areas, especially language rights, the policy regimes of the two levels of government conflict. The federal Official Languages Act (1985), based on a conception of Canada as a bilingual country, defines English and French as official languages in all activities of the federal government. Citizens have the right to use either language in Parliament and federal courts and to receive services from federal agencies in the official language of their choice. In contrast, language legislation of the Québec provincial government defines French as the sole official language in the operations of the provincial government and deploys various measures to give priority to French in public education, commercial signs and the workplace.

Beyond the domain of language, most culturally sensitive areas fall under the jurisdiction of the Québec government, and its legislation and policies reflect the distinct Québécois culture. The asymmetric devolution of additional authority to Québec in the area of immigration allows Québec to give priority to French-speaking immigrants and to establish a distinct intercultural model of integration policies, which stands in contrast to the federal model of multiculturalism. As we shall see in more detail in Part II (2), the interculturalism approach has seen the introduction of restrictions on religious dress in the public space, efforts which have been criticized in the rest of the country but supported by the majority of the Québec population.

Ethnoracialized Minorities

The Constitution of Canada entrenches a number of provisions of particular relevance to ethnoracialized minorities. Section 2 of the Charter provides protection for fundamental freedoms including those of conscience, religion, belief, opinion and expression, and s. 14 entitles participants in legal proceedings to interpreters. Section 15 protects against discrimination based on “race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.” Importantly, s. 15 (2) provides that ameliorative programs aimed at addressing disadvantage are not discriminatory. Finally, s. 27 stands as a broad interpretive section for the entire document, providing that the Charter will be interpreted in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of Canada’s multicultural heritage. However, this section is a broad interpretive provision and has rarely been used directly in adjudicating claims involving other Charter sections.

There are, however, significant limitations that restrict the strength of these Charter provisions. Section 1 states that the Charter “guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” A complex jurisprudence has developed to guide courts in interpreting reasonable limits to rights. Additionally, religious freedom, the right to an interpreter and equality rights are subject to s. 33 of the Charter, which allows a provincial or federal government to override rights for a period of five years (renewable) by a simple legislative majority.

At the level of general legislation, Canada has an extensive multiculturalism program that was first announced in 1971 and is anchored in the Canadian Multiculturalism Act (1988).

The immediate goal of multiculturalism was to change the terms of integration for immigrants, laying to rest ideas of assimilation and creating space for ethnic minorities to celebrate aspects of their traditional culture and traditions

while participating in the mainstream of society.

Multiculturalism was also part of a broad state-led redefinition of national identity, an effort to diversify the historic conception of the country and build a more inclusive nationalism—a national identity reflective of Canada’s cultural complexity. Elements of this program include funding for ethnic minority cultural organizations, requirements that public broadcasting include individuals from diverse backgrounds, inclusion of diversity in the school curriculum and broad acceptance of exemptions to dress codes for religious dress.

Although the multicultural approach to pluralism is widely celebrated in English-speaking Canada, Québec has charted a different course, known as interculturalism, which has two features that set it apart from the federal approach. As we have seen, federal multiculturalism promotes the choice of two official languages, English and French, while the Québec model defines French as the common language in the province. Beginning in the 1990s, Québec also developed a distinct approach to diversity. While federal multiculturalism was seen as implying the equal recognition of all cultures, negating the centrality of any particular culture, Québec’s intercultural approach defines the francophone majority culture as the central hub towards which other minority cultures are expected to move. Part II (2) discusses how the differences in these two legal approaches to pluralism have worked out in practice.

Canada also has employment equity legislation, although these programs have significant limitations. While provincial and federal human rights codes exist to address discrimination by private employers and voluntary associations, the federal Employment Equity Act (1995) promotes proactive hiring practices for both racialized minorities and Indigenous persons in the federal public service and federally regulated workplaces. Although no specific quotas are set for employers as a whole, they are expected to work toward targets based on labour-market availability thresholds. Employers must prepare reports on the number of people in designated groups employed at different levels of their organizations and have a plan in place to respond to inequalities. Technically, the legislation applies only to federally regulated industries, which together employ about 10 percent of the Canadian workforce. The fact that provinces other than Québec do not have parallel legislation means that most employers are not covered. This weakness is partially mitigated by the Federal Contractors Program, enacted in 1986, which requires larger employers wishing to bid on federal contracts or receive federal grants to develop employment equity programs designed to identify and eliminate discriminatory barriers. In 1995, a new Employment Equity Act was passed, which improved compliance provisions by giving the Canadian Human Rights Commission the authority to conduct audits and creating a tribunal to enforce compliance. In 1999, the Commission found that many employers set goals that were lower than the labour-force availability of the designated groups.

Finally, criminal law sanctions prohibiting hate speech protect diverse groups. Prohibited speech includes advocacy of genocide and inciting hate against an identifiable group in a manner that is likely to lead to violence. Anti-hate provisions have generally been upheld by the courts when they have been challenged, and judges can impose higher penalties when crimes have been motivated by hate.

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous Peoples have never been recognized as founding peoples of Canada. They lack the veto over constitutional change that Canadian provinces enjoy, and their inclusion in negotiations over constitutional amendments has often been limited. Nevertheless, the rights of Indigenous Peoples are protected in both s. 25 of the Charter and s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The latter section has been much more important, entrenching existing “Aboriginal and treaty rights,” including rights attained by land claim agreements. However, judicial interpretation has also limited this provision. For example, while s. 35 Aboriginal and treaty rights fall outside the Charter and therefore beyond the reach of the reasonable limitations test in s.1 of the Charter, the Supreme Court of Canada has effectively imported the same approach into s. 35, allowing governments to limit rights where doing so amounts to a justifiable interference (R. v. Sparrow). Despite these limitations, there have been significant court rulings in Canada, several of which have been critical to Indigenous land rights (Delgamuukw v. British Columbia). In Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014), the Supreme Court recognized Indigenous title to unceded traditional lands but also set out grounds on which that title could be overridden by the public interest.

Nonetheless, colonial era laws, such as the Indian Act, still place significant restrictions on the exercise of self-determination by Indigenous nations.

Of particular note is the control that the Indian Act grants to the federal government over who can claim Indian status for legal purposes, and as a result who has access to the benefits and rights afforded by treaties negotiated with the federal government. Historically federal government control over membership has been exercised to the disadvantage of Indigenous women, with women who married non-Indigenous men being forced to give up their status, while men who married non-Indigenous women were not required to do so. A challenge by Sandra Lovelace Nicholas to the UN Human Rights Commission led to changes to status to allow women who married non-Indigenous men to keep their status (and those who has lost their status due to previous marriages to regain it). Status, however, is differentiated into two different categories known as 6 (1) and 6 (2) status. Individuals end up with 6 (2) status if they have only one parent who has status, and such individuals may not pass their status on to their children unless both parents of the child have status. The result of these rules is a loss of control by Indigenous communities over who can claim the legal rights entitled to members of their communities by treaties and the perpetuation of the gender-discrimination inherent in the marrying out rule.

The most persistent claims for Indigenous recognition and protection have taken the form of demands for self-determination. The federal government has responded with self-government and land settlement agreements, which offer delegated powers to Indigenous communities. While a Comprehensive Land Claims Policy was created in 1973, the federal government’s 1995 Inherent Right Policy provides a framework for the negotiation of self-government agreements in recognition of the collective right of Indigenous Peoples to govern their own internal community affairs. More limited intergovernmental agreements are also available for the delegation of federal power over specific community issues, without entering into self-government agreements. Importantly, the Inherent Right Policy explicitly rejects Indigenous sovereignty.

Finally, Canada’s legal system offers criminal sanctions to address violence against women. Nonetheless, women across Canada experience gender-based violence. Indigenous women experience particularly high rates of gendered abuse. They are almost three times more likely to be violently victimized than non-Indigenous women with 79 percent of those acts being committed by male perpetrators. In 2015, Indigenous women were six times more likely to be murdered than non-Indigenous women and more than two-and-a-half times more likely to be murdered than Indigenous men. Additionally, Indigenous women experience considerable racialized and sexualized violence at the hands of police, which often goes unreported or is handled through employee discipline procedures rather than through criminal charges. While Canada has taken steps to investigate violence against Indigenous women through its National Inquiry into MMIWG, leaving police authorities, including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), to investigate officers accused of violence against women remains a serious hurdle to addressing gendered and racialized violence.

3. Inclusive Citizenship

Average Score: 9

Québécois | Score: 10

Ethno-racialized minorities | Score: 8

Indigenous Peoples | Score: 9

Citizenship is a primary mechanism by which states recognize an individual as deserving of formal rights and protections as well as being a full member of that country. Unlike many others, this formal dimension of pluralism varies relatively little among different minorities in Canada.

Québécois

Like all other Canadians, Québécois who are born in Canada or have at least one parent with Canadian citizenship are considered citizens of Canada. The status of Quebecers as full citizens within Canada dates to the approach of the Britain Parliament in the Quebec Act (1774), in which Québécois were considered to be subjects of the British Crown, a status that, therefore, predated the emergence of a distinct Canadian citizenship for both Québécois and anglophone Canadians. As Canada developed its own nationality and citizenship laws in the 1940s, Québécois and other francophone Canadians held the same status as anglophone Canadians.

Ethnoracialized Minorities

Canada has adopted a jus soli approach to citizenship, ensuring that people born in the country have an automatic right to Canadian citizenship. Accordingly, members of ethnoracialized minorities born in Canada are automatically considered to be citizens.

For members of ethnoracialized minorities coming to Canada as immigrants, access to citizenship is more complicated and depends on the interaction between immigration law and citizenship law.

For immigrants admitted as permanent residents, access to citizenship is relatively straightforward, and rates of citizenship acquisition are generally very high. The Migration Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) notes that in 2011, fully 92 percent of foreign-born individuals had become citizens after 10 years of living in the country. Bloemraad attributed the high level of citizenship acquisition in Canada to a multicultural immigrant integration policy that actively promotes citizenship acquisition. In addition, Canada has accepted dual citizenship since 1977, ensuring that newcomers do not have to surrender their past to become Canadians. In 2014, the Conservative government enacted reforms that slowed the process of citizenship acquisition somewhat, although the succeeding Liberal government partially offset the changes. As a result, permanent residents have to be in Canada for three out of the last five years to apply for citizenship.

Access to citizenship for other categories of immigrants is much more difficult. The Temporary Foreign Worker’s Program (TFWP) along with the International Mobility Program allows migrants to enter Canada for limited periods of time in order to work, usually for specified employers. Most low-skilled individuals who enter Canada through the TFWP to work in areas such as agriculture or retail are unable to get permanent residency and must leave Canada once their contracts are complete. The Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) is notable in this regard. Prokopenko and Hou found that after 10 years of participation in SAWP, only 2 percent of workers had secured permanent status. The Caregiver Program stands as an exception. Workers in this program can apply for permanent status after two years or 3900 hours of work experience. Between 1990 and 2014, 86.9 percent of those admitted under the Live-in Caregiver Program had secured permanent status after 10 years. As of 2016, this category of workers is also required to satisfy a language requirement and have at least one post-secondary education credential to qualify for permanent residency. In April 2021, the federal government introduced a pathway to citizenship for three streams of temporary foreign workers, one for workers in health care, one for workers doing what the government classifies as essential jobs and one for international students.

In the aftermath of 9/11, immigration became increasingly securitized and racialized persons became increasingly associated with criminality and threats to security. In 2015, legislation came into effect allowing Canada to strip the citizenship of dual nationals convicted of terrorism-related offenses as well as those found to have gained citizenship status through fraud or false representation. The law concerning dual citizens was repealed in 2017 having only been applied in one case.

Indigenous Peoples

Historically, the efforts of settler governments to dismantle Indigenous nations operated through citizenship rules. The Gradual Civilization Act (1857) and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act (1869) offered Indigenous men the “privilege” of attaining citizenship in return for the forfeiture of their treaty rights. When voluntary enfranchisement failed, the first Indian Act, passed in 1876, instituted compulsory enfranchisement upon certain conditions being met, conditions that most Indigenous men ensured they did not meet. Prior to 1960, the Indian Act considered members of First Nations as wards of state as opposed to citizens with the rights held by others. Since then, Indigenous persons have held voting rights on the same basis as all other Canadian citizens. In the contemporary context, like Québécois, Indigenous persons born in Canada or born to at least one Canadian parent are automatically considered citizens, and, as noted at the outset of this report, scoring on this indicator is based on current rather than historical practice.

However, the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and Canadian citizenship is complicated by Indigenous claims to nationhood.

First Nations leaders prefer to define the relationship with Canada as one between separate nations and insist that political relations should proceed on a nation-to-nation basis.

Accordingly, many Indigenous individuals do not define themselves as citizens of Canada and choose not to vote in Canadian elections.

Citizenship rights for Indigenous nations that span both sides of the Canada-United States (US) border are especially complex. The US recognizes the right of Indigenous individuals born in Canada to freely enter and work in the US under the Jay Treaty. However, the Canadian government does not reciprocate, as it considers the Jay Treaty to have been abrogated by the War of 1812. Members of First Nations whose territory crosses the Canada-US border and who are born in the US are thus not automatically considered Canadian citizens and do not have an automatic right to enter Canada even though significant portions of territory claimed by their communities are in Canada. This is particularly an issue for the Mohawk of Akwesasne whose territory spans both sides of the Canada-US border.

The issue emerges most graphically in the use of passports. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, which spans the US-Canada border, issues its own passports. Canada (as well as many other states) does not recognize these passports, which can create challenges for Haudenosaunee individuals travelling on them. Both the Iroquois Nationals lacrosse team and a delegation to a climate change conference in Bolivia have had difficulty entering countries and returning to Canada because of their decisions to travel on Haudenosaunee passports.

II. Practices

While commitments are important, pluralism requires sufficient political will and action to realize commitments in practice. This dimension includes three measures for assessing the extent to which practices of the state reflect a desire to build more inclusive and equal societies.

4. Policy Implementation

Average Score: 6.5

Québécois | Score: 9

Ethno-racialized minorities | Score: 7

Indigenous Peoples | Score: 4

Not surprisingly, there are continuing debates about whether the legal commitments to pluralism are fully implemented in practice. Minority groups and their supporters highlight many places at which Canada falls short. At the risk of oversimplification, one might conclude that the commitments to Québécois have been more fully realized than commitments to other groups, especially Indigenous Peoples.

Québécois

In practice, the federal system provides Québécois with a powerful instrument of self-governance. The general division of powers in the federation is comparatively decentralized and asymmetric arrangements have enhanced the powers of the Province of Québec over culturally sensitive policies including immigration. Since the Québec referendum of 1995, when the separation of Québec from Canada was defeated by the slimmest of margins, a new equilibrium seems to have emerged. The federal government and other provinces have accepted elements of asymmetric decentralization to Québec. The protracted political battles over the division of jurisdiction, which dominated Canadian politics for decades, have eased and support for separation among Quebecers has declined. Nevertheless, Québec remains insistent on preserving its separate cultural space and resists federal interventions—as in the case of the Québec policy on religious dress.

Canadian federalism gives all provinces control over education and social services, which Québec has managed with an eye to preserving its distinct identity. For example, Québec has developed an expansive daycare program that is unique within Canada. In addition, the federal system is also asymmetric, allowing Québec greater policy space than enjoyed by other provinces. For example, Québec operates its own contributory public pension, the Québec Pension Plan, while the rest of the country relies on the Canada Pension Plan, which operates through joint federal government and provincial agreement.

Québec has also negotiated a level of control over immigration that is unique amongst the Canadian provinces. The Gagnon-Tremblay-McDougall Agreement allows the province to select economic immigrants coming to the province, allowing Québec to give priority to immigrants who speak French. The province also has full control over immigrant integration policy and has used this control to pursue an integration policy that emphasizes integration into a majority francophone society.

Québec’s approach to immigrant integration has often deviated from the multicultural approach that characterizes immigration policy in much of the rest of Canada.

While federal politicians have expressed opposition to aspects of Québec’s approach to religious diversity, such as its restrictions on provincial public servants’ right to wear religious symbols, they have generally respected Québec’s jurisdiction to pass such legislation.

There is further broad acceptance of official bilingualism in Canada, protecting the use of French within federal institutions, though there is less public support for bilingualism in Western Canada. Since the mid-1960s, the federal government has put considerable effort into making the federal civil service bilingual, ensuring that language is not a barrier to Québécois’ and other French-speaking Canadians’ access to federal government jobs. The federal government has also funded bursary programs, such as the Explore program, that have sought to increase the number of Canadians who can speak both official languages. Despite the funding of such programs, the number of bilingual Canadians only grew slightly over the 2011¬¬–16 period.

Ethnoracialized Minorities

As we saw in Section I, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) protects basic freedoms but also allows significant limitations that restrict the strength of those guarantees. In practice, action on anti-discrimination remains extensive. On a number of issues, the Supreme Court has been able and willing to protect minority rights. The courts have upheld criminal provisions banning hate speech and have generally protected religious exemptions to dress codes. This protection includes striking down a decision by the Conservative government in 2015 to ban niqabs from citizenship ceremonies.

The multiculturalism program has been consequential. Judged by its original goals, the multicultural approach to diversity has been a comparative success. It has helped change the terms of integration for immigrants, which has helped strengthen their sense of attachment to the country.

In addition, multiculturalism has become deeply embedded in Canadian culture, at least in English-speaking Canada, and has contributed to a more inclusive form of Canadian national identity.

Nonetheless, the limits of multiculturalism have also become apparent over the years. The policy has not eliminated racial discrimination in Canada, and, at times, the focus on the affirmation of difference and anti-racism initiatives has been displaced by a growing emphasis on integration and the creation of active citizens with an attachment to Canada. Moreover, the commitment to diversity seems fragile at times, most recently in the case of Muslim Canadians, arguably the least popular religious minority in the country. The Conservative government, which held power from 2006 to 2015, introduced a ban on the wearing of the niqab during citizenship ceremonies and passed the Zero Tolerance for Barbaric Cultural Practices Act (2015), which used criminal and immigration law to target practices associated with Muslim immigrants. While the ban on the niqab during citizenship ceremonies was struck down by the courts as noted above, and references to “barbaric cultural practices” were removed from the Act by the subsequent Liberal government, the racialized stereotypes on which it was founded undoubtedly persist.

These issues have been most heated in Québec. As we saw in Part I (2), Québec rejected the multicultural approach in favour of interculturalism. In the early years, there was considerable debate about whether federal multiculturalism and Québec interculturalism actually differed much on the ground. In the 2000s, however, the differences were magnified by the growing salience of religion. Québec has come to define secularism as a central feature of Québec culture, and many Québécois fear secularism is undermined by the greater religiosity of some minorities. In 2019, the government of the Coalition Avenir Québec succeeded in passing the Loi sur la laïcité de l’État (Law on the Secularism of the State), which prevents new public servants in positions of authority, including teachers, police officers and judges, from wearing visible religious symbols during working hours. It also requires faces to be uncovered to both give and receive certain public services. To pre-empt legal challenges, the government took the dramatic step of invoking the notwithstanding clause, shielding the legislation from Charter challenges based on religious freedom and religious equality for five years. The law has a disproportionate impact on Muslim women who choose to wear hijabs or niqabs, though Sikh men who choose to wear turbans and Jewish men who choose to wear kipahs are also negatively affected. Though the law was opposed by two opposition parties in the provincial legislature (the Québec Liberals and Québec solidaire), support by both parties’ versions of legislation limiting civil servants and those receiving public services from wearing religious symbols makes it likely that this legislation will survive future governments.

Finally, recent practice suggests that the employment equity programing established by the federal government does help, even though it applies only to federally regulated employers, a small portion of the total. In the federally regulated private sector, the representation of racialized employees did meet the labour-market availability threshold. Equity measures also matter in the public service. National data from 2011 found no wage gap between Canadian-born and immigrant men in the public service but did find a 4.1 percent gap in favour of Canadian-born men in the private sector. However, Canadian-born women earned more than immigrant women in both sectors.

Indigenous Peoples

As we have seen, Indigenous Peoples have never been recognized as founding peoples of the country called Canada or given the same constitutional protections for their languages and traditional beliefs as English and French Canadians have. Although decisions of the Supreme Court, including those discussed earlier, have breathed considerable life into the idea of Aboriginal and treaty rights, much is left open for determination in practice through ongoing legal and political processes.

Competing sovereignty claims have underpinned Indigenous-settler government relations.

Despite commitments to reconciliation, Canadian governments have been reluctant to acknowledge Indigenous sovereignty claims when such claims conflict with their own.

Canadian courts have demonstrated unwavering support for Crown sovereignty, interpreting s. 35 in ways that divest Indigenous rights claims of their wider political character by limiting s. 35 Aboriginal rights to a list of authentic practices, customs, and traditions that were integral to distinctive cultures at the time of European contact.

The failure to acknowledge Indigenous sovereignty has led to conflict over resource and other development projects that affect Indigenous lands. Significant court rulings in Canada have protected Indigenous land rights (Delgamuukw v. British Columbia). In Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, the Supreme Court recognized Indigenous title to unceded traditional lands but also set out grounds on which that title could be overridden by public interests. The result has been a high level of uncertainty and recurring conflicts during negotiations over resource development projects. While the Canadian government has stated its desire that negotiations be based on the principle that Indigenous nations should give free, prior and informed consent to development, in practice that principle has not been a basis for negotiations. The Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests) (2004) case recognizes a duty to consult with Indigenous nations when projects affect their territory but does not grant First Nations a veto over such projects. The extent to which the government needs to engage in consultations and the required level of response to nations’ concerns is vague. It is notable that a 2018 court challenge to the Trans Mountain pipeline development successfully claimed that consultations with Indigenous groups were inadequate but that after a second round of consultations, the Federal Court of Appeal rejected a second challenge by Tsleil-Waututh Nation that consultations had been inadequate.

Resource revenue-sharing agreements between Indigenous nations and provincial or territorial governments exist to share public revenues generated from resource development, including royalties and taxes. In addition, since the late 1980s, Indigenous communities have entered into privately negotiated Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs) with industry to govern the extraction of resources from traditional territories, especially in the mineral-rich North. These agreements offer benefits such as employment quotas, financial compensation, joint venture opportunities and skills training to aid Indigenous communities. IBAs are often lauded for being in keeping with self-determination rights because they are most often negotiated without government participation. However, Cameron and Levitan contended that because IBAs contractually limit resistance to resource extraction through confidentiality provisions and privatize the Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate where Indigenous rights may be infringed by resource development, a comprehensive federal policy to guide IBAs between Indigenous communities and industry partners must be developed by the federal government.

Although most attention falls on issues of resource development, there are many other government commitments that have not been met, from the honouring of treaty terms to the federal government’s failure to ensure clean drinking water in communities living on reserves (land set aside by the Canadian government for use by First Nations). At the same time, persistent delays in negotiating agreements with Indigenous Peoples suggest a failure to commit the resources necessary to complete agreements in a timely manner. The Akaitcho land claims process, which negotiators had hoped to conclude in 2020, and which was sidelined by COVID-19, provides one example. Formal negotiations to complete the agreement commenced in September 2001.

5. Data Collection

Average Score: 6.5

Québécois | Score: 9

Ethno-racialized minorities | Score: 7

Indigenous Peoples | Score: 4

The Canadian Census collects extensive data related to pluralism. This includes data on language (both official and minority languages), identification with Indigenous Peoples (broken down by Indigenous nation), visible minority status (also broken down by identity), ethnic identification and immigrant status (broken down by country of origin). Anonymized census data is made publicly available and includes a broad range of variables such as geography, income and employment, data about household dwellings, education and marital status. Because the census is mandatory, these data are very reliable, allowing for sophisticated data analysis on pluralism by academics, policy-makers, advocates and activists. In addition, data on minority groups can be broken down by gender in order to facilitate intersectional analyses.

Statistics Canada has also conducted a number of dedicated surveys related to pluralism. These include the Ethnic Diversity Survey, released in 2003; the Aboriginal Children’s Survey, released in 2008; the Aboriginal Peoples Survey conducted every five years; the General Social Survey (GSS) conducted every five years; an immigration and diversity projection; and an occasional minority and second language education survey.

As noted in a previous section, the Employment Equity Act requires the federal public service and employers in federally regulated industries (about 10 percent of the workforce) to report regularly on diversity amongst their employees and measures that they are taking to ensure proportional representation of both visible minorities and Indigenous persons.

Despite these multiple sources of data, there is still a major gap in the adequacy of data collection among different minorities and Indigenous Peoples.

Québécois

Data collection regarding Québécois in Canada benefits from norms surrounding the collection of regional and provincial data as well as data on language. As a result, most data sets in Canada, including the census data mentioned above, can be used to facilitate analysis focussed on Québec as province, francophones across all of Canada or francophones within Québec. Recently, the Government of Québec used Statistics Canada data and projections (coupled with a 2018 survey on language spoken at work) to argue that the use of French was declining in Montréal. This serves as an instance where Statistics Canada data has been used to inform debate on a sensitive subject matter in the province.

Ethnoracialized Minorities

The Canadian Census collects data on whether individuals are immigrants, what languages they speak (including non-official languages) and whether individuals identify as “visible minorities.” This allows for analysis of differences in socio–economic conditions between immigrants and non-immigrants (as well as with respect to second-generation immigrants), minority language and ethnoracial identities. The potential for analysis of these differences using government data is limited to those socio–economic categories surveyed in the census such as education and income. Analysis of other differences depends upon dedicated government studies like the ones noted above, which are conducted at less frequent intervals, or as academic and other non-governmental research. It should be noted, however, that the census groups some “visible minorities” much more broadly than others.

Nonetheless, there are significant gaps in data collection.

COVID-19 brought Canada’s failure to track health inequities among racialized people into stark relief, highlighting the fact that public health authorities do not routinely collect ethnicity and race-based health data.

Indeed, there was initially some resistance to gathering that data among provincial and federal authorities. In April 2020, Chief Public Health Officer of Canada Dr. Theresa Tam stated that there were “no plans” to add more social determinants of health to the case reporting form used to collect COVID-19 data, while Dr. David Williams, Ontario’s then chief medical officer, stated that those most at risk were the elderly and people with underlying health issues, regardless of race or ethnicity. This resistance was particularly troubling given the early data coming out of the United Kingdom (UK) and the US showing that racialized minorities were harder hit by the virus. Though the first case of COVID-19 was reported by Health Canada on January 25th, 2020, both the federal government and Ontario government waited until June to announce that they had begun working on plans to collect ethnicity and race-based data. In October 2020, Statistics Canada released data echoing the findings in other countries. Using neighbourhood-level data from the 2016 census, the research confirmed the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on neighbourhoods with higher percentages of racialized minorities.

While much harder to find, there is some individual-level data confirming disparities in COVID-19 infections based on racialized status. For example, the City of Toronto began collecting data on ethnoracial identity in May 2020. As of May 31th, 2021, the rate of COVID-19 infections was two-and-a-half times higher among those identifying with racialized groups compared to white people, while the rate of hospitalization was 2.7 times higher after age standardization. Members identifying as Latin American had the highest overall case rate among all groups followed by people identifying as Arab, Middle Eastern or West Asian; Southeast Asian; South Asian or Indo-Caribbean; and black. Data on Indigenous Peoples were not reported. Data from Manitoba, the first province to start collecting race-based data, indicates that 51 percent of people testing positive for the virus between May 1st to December 31th, 2020, were black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC), though they constituted only 35 percent of the population. People identifying as African, Filipino, North American Indigenous and South Asian were overrepresented in the COVID-19 case count data, while white individuals were underrepresented by 16 percentage points.

Data on the criminal justice system are problematic.

The overrepresentation of Indigenous and black people in prisons is well documented because correctional data on race and Indian ¬status are consistently collected.

However, the availability of other race-based criminal justice statistics is limited. In many cases, police simply do not collect the information, and when they do, they often refuse to report it. Information about¬ victims/offenders has been routinely withheld; a study in 2014 concluded that close to 60 percent of Canadian police forces withhold that information as regular police practice. In the wake of a troubling Ontario Human Rights Commission report finding that black individuals are 20 times more likely than white individuals to be shot and killed by Toronto police, the Toronto Police Board committed to collecting and reporting race-based data, starting with “use of force” incidents in January 2020. Similar problems mark efforts to track the existence of a racialized school-to-prison pipeline; there is little empirical research tracking school discipline or its consequences for racialized youth. However, a 2020 review of the Peel District School Board in Ontario, where 83 percent of students are racialized, found that black students received 22.5 percent of all suspensions yet comprised only 10.2 percent of the student population. The report also indicated that black male students were particularly overrepresented among student suspensions, expulsions, exclusions from the classroom and streaming into lower education tracks.

Indigenous Peoples

There are particular gaps in data collection regarding Indigenous communities and even instances of state actors misrepresenting data or failing to properly use and report data. In tracking the high school graduation rate of on-reserve students between 2011 and 2016, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) reported a 46 percent graduation rate. According to Canada’s Auditor General, however, the actual graduation rate was 24 percent. The ISC had excluded all students who withdrew from high school in grades 9, 10 and 11 from its calculation.

More generally, Indigenous data collection is marked by the failure to consistently differentiate between individuals living on-reserve and off-reserve, to disaggregate First Nations data to the community level and to employ uniform definitions across databases. Federal and provincial authorities do not gather data on Indigenous identity in a coordinated and consistent manner. Failing to do so can have grim consequences: the absence of data on Indigenous identity in the child welfare system has been cited as the primary reason why the National Inquiry into MMIWG could not definitively determine the number of individuals who were murdered or disappeared.

In the realm of health, government failures to collect ethnicity and race-based COVID-19 data are even more troubling given that Indigenous people were six-and-a-half times more likely than non-Indigenous persons to be admitted to an ICU during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Despite this fact, no agency existed to reliably record the correlation between Indigenous identity and COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic, with the majority of Indigenous Peoples, including those living on reserve, relying on public health authorities for care.

Manitoba was the first province to ask patients to self-identify as First Nations, Métis or Inuit on April 3rd, 2020, after entering into a data sharing agreement with the province’s First Nations leadership.

Early data collected by the ISC did not include Indigenous Peoples living in urban and rural areas, or Métis persons, despite outbreaks in communities with large Métis populations, such as La Loche in Saskatchewan. Additionally, the COVID-19 data reported by the ISC did not align either with information coming out of Indigenous communities or with publicly available information. The latter suggested that cases in Indigenous communities were three times higher than the number reported by the ISC.

The COVID-19 crisis also highlights the complexities inherent in the relationship between Indigenous sovereignty and data collection. While British Columbia health authorities withheld COVID-19 data from local Indigenous communities, Manitoba’s Indigenous leaders invoked their data sovereignty to deny access to their own people. There is a need to develop data collection strategies that respect the self-determining character of Indigenous Peoples and the Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) Principles. The OCAP principles, which ensure First Nations control over data collection processes and the way in which data are used and stored, are central to the mandate of the First Nations Information and Governance Centre, a non-profit First Nations organization whose mandate is to build capacity and provide credible information on First Nations. The need to incorporate OCAP principles into data collection strategies, whether through increasing the capacity of First Nations to collect their own data or through data sharing agreements with government partners, is also being widely recognized by other organizations, including the Canadian Institute for Health Information and British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner.

6. Claims-Making and Contestation

Average Score: 7

Québécois | Score: 9

Ethno-racialized minorities | Score: 7

Indigenous Peoples | Score: 5

The ability of groups to make claims is a critical component of a healthy pluralistic society. All the major minority groups in Canada actively seek to advance their interests and concerns in political debate, but their ability to do so varies significantly among them.

Québécois

The claims of Québécois in the federal system have been advanced through electoral politics and federal–provincial relations. The early history of separatist protest did include episodes of violence and the subsequent military suppression of civil rights. However, after the emergence of a major sovereigntist party, the Parti Québécois, advocacy of Québec separatism has proceeded through peaceful means, including two referenda on separation. Advocacy of Québec nationalism within the federation affords Québécois a nation-building tool to protect their distinctive culture, enhance the province’s state capacity, and differentiate Québec from its provincial counterparts.

Québec’s central place in electoral and parliamentary politics ensures that governments are responsive to Québécois’ concerns.

The reality that winning in Québec was pivotal to winning federal elections for much of twentieth century gave federal political parties a powerful incentive to be responsive to the concerns of Québécois voters.

The Québec provincial government also acts as a powerful advocate for Québécois interests exerting an important influence over intergovernmental politics. Finally, expectations that appointments to the federal Cabinet will be broadly representative of Canada’s regional diversity ensures that there are Québécois represented in the federal executive.

Ethnoracialized Minorities

Ethnoracialized minorities have tended to advance their claims principally through electoral and judicial strategies. Their concentration in competitive constituencies in the Greater Toronto Area and the suburbs of Vancouver sensitizes parties to their concerns and ensures numerous candidates from their communities are elected to office. Increasingly, there is an expectation that ethnoracialized individuals be represented in both federal and provincial Cabinets, providing an additional avenue through which groups can assert their interests. Representation, however, is not uniform across different ethnoracialized minority groups, with some groups having a great deal of representation in federal and provincial Cabinets and others having little to none. In addition, racialized minorities, in particular, have relied on judicial processes to advance claims rooted in their cultural distinctiveness, especially their religious differences.

Ethnoracialized minorities also engage in protest politics. This form of claims making varies from group to group and even within groups. To take one example, Korean Canadians are noted for a style of claims-making that is both culturally and politically conservative. The Ontario Korean Businessmen’s Association, one of Ontario’s most vocal groups, routinely issues press releases, engages in public awareness campaigns and sends delegates to Parliament, along with organizing large-scale demonstrations championing the interests of small retailers. By way of contrast, the Black Lives Matter movement has engaged in grassroots protest politics to highlight police surveillance and violence against black Canadians. State surveillance, to which other racialized groups have also been subject, limits dissent and activism, generating a dynamic between repression and activism. This dynamic helps explain why recent immigrants, including black African immigrants, largely abstain from protest politics. The country of origin also matters.

Research suggests that immigrants from repressive regimes are less inclined than both the local population and immigrants from less repressive regimes to engage in public activism.

Despite such constraints, protests emerged in most Canadian cities in summer 2020 as part of the global Black Lives Matter response to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. Protests highlighted a number of instances of police violence against ethnoracialized people and Indigenous Peoples, including the killing of Chantel Moore in Edmunston, New Brunswick, and the death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet in Toronto.

While Black Lives Matter protests (in 2020 and before) in Canada have not seen the same level of police violence as in the US, there have been instances in which such protests have been attacked by police, and distrust of the police amongst Black Lives Matter demonstrators is high.

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous claims-making is marked by a mix of formal negotiation, litigation and protest politics. Activists have routinely engaged in blockades, barricades and demonstrations to protest developments on disputed lands. These efforts have not gone without violence, however. During the 1990 Oka Crisis in Québec, police used tear gas and concussion grenades, which instigated gun violence between police and Mohawk protestors. In 2012, the Idle No More campaign emerged in response to federal legislation that decreased Indigenous control over reserve lands and exempted many development projects from environmental assessment. The campaign erupted via social media, leading to national days of action that included demonstrations on Parliament Hill, blockades, train and traffic stoppages, and hunger strikes. The movement succeeded in forcing a meeting with then Prime Minister Stephen Harper and resulted in the negotiation of a declaration of commitment with both opposition parties to address a broad range of issues affecting Indigenous Peoples.

While the federal government’s land claims and self-government agreement processes exhibit a commitment to the negotiation of Indigenous self-government, there remains a gulf between the Canadian state and a growing Indigenous Resurgence movement that is turning its back on state engagement and the Canadian legal system in favour of a grassroots, non-statist path to self-determination. This trend to claims making through protest has been highly contentious. Blockades set up in 2019 and 2020 by the Wet’suwet’en in protest of the Coastal GasLink Project in Northern British Columbia were dismantled by RCMP in tactical gear despite the protesters at the blockades being peaceful. Journalists were removed from the area by RCMP as the blockades were being dismantled. The dismantling of these blockades triggered cross-country protests and blockades by Indigenous groups and their allies, including blockades of major rail lines across the country, the port of Vancouver and the BC Legislature. In response to protests in Alberta held in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, the province passed the Critical Infrastructure Defence Act (2020). Predicated on disrupting protest activities, the legislation authorizes fines and imprisonment for persons who block, damage or unlawfully enter places deemed to be essential infrastructure or obstruct their construction and maintenance. Alberta’s legislation is already facing a Charter challenge by the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees on the grounds that it violates the right to peacefully assemble and to engage in collective bargaining activities.

Tensions have not been limited to the West of the country. In 2020, violent protests against Mi’kmaw lobster fishing rights in Nova Scotia saw vandalism and destruction of Mi’kmaw property and threats to individuals’ safety by non-Mi’kmaw protestors. These instances mark a troubling increase in violent conflict between Indigenous groups claiming rights and interests and police and non-state actors opposed to them.

III. Leadership for Pluralism

Pluralism requires leadership from all sectors in society, including non-state actors that may adopt policies and practices that affect groups’ ability to fully participate in society. This indicator assesses four critical non-state actors.

7. Political Parties

Average Score: 8

Québécois | Score: 9

Ethno-racialized minorities | Score: 8

Indigenous Peoples | Score: 7

Building and maintaining a healthy pluralism requires leadership and support from across society. In Canada, elites in many sectors are supportive of pluralism in principle, and active leadership tends to come from institutions that have a serious self-interest in being responsive to minorities. Primary among these are political parties.

In Canada, active leadership for pluralism comes primarily from political parties. However, the level of engagement varies from one minority to another, depending in part on the size of the minority.

Québécois

As Québec contains 78 of 338 seats in the Canadian Parliament, Canadian political parties have a strong incentive to be responsive to Québécois’ interests. Prior to 1993 at least, the party that won large numbers of seats in Québec usually formed the government, which served to increase the incentives to pay attention to Québec issues. This has manifested itself in several ways. Both Conservative and Liberal governments have recognized Québec’s unique place in Canada (the Liberals doing so in 1995 and the Conservatives in 2006). Each of the major federal parties has made a significant effort over the past two decades to appeal to Québécois voters. For the Conservatives, this took the form of commitments to recognize Québec as a nation, give it a seat on the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and respect provincial autonomy in areas of provincial jurisdiction. For the New Democratic Party (NDP), efforts to win votes in Québec led to promises to allow Québec to opt out with compensation of any new federal programs in provincial jurisdiction and to respect a “50-plus-1” vote for Québec sovereignty in the event of a third referendum on the matter. The Liberals, in contrast, have relied on their traditional strength in Québec (especially amongst federalists) to make the case that they have a unique ability to represent those Quebecers who want Québec to have a strong place within Canada.

The need to win seats in Québec leads all parties to try to ensure that Québécois individuals are represented as prominent members of their parties.

The Liberal Party has a tradition of alternating between anglophone and francophone (or at the very least Québec-based) leaders. While the Conservatives and NDP do not have the same tradition, they regularly recruit high-profile Québécois candidates and often designate Québec “lieutenants” to ensure the province is represented with the party leadership. Recent examples of such individuals include Denis Lebel for the Conservatives and Alexandre Boulerice for the NDP.

The Canadian party system has seen regional parties emerge that have distinct positions on the status of Québec. The Bloc Québécois, a Québec separatist party, held the plurality of the federal seats from Québec from 1993 to 2011. The party struggled in the 2011 and 2015 elections before re-emerging as the second largest federal party in Québec in 2019. In contrast, the Reform Party emerged during the late 1980s and early 1990s in part as a reaction to efforts by the Progressive Conservative government at the time to recognize Québec’s distinct identity. The party saw most of its success in Western Canada resulting from strong positions it took against any recognition of Québec as different from the other provinces in the country. After rebranding as the Canadian Alliance, the party merged with the Progressive Conservatives in 2003 to form Canada’s current Conservative Party. While the majority of members of the Conservative Party came from the Canadian Alliance, strategic considerations forced the Conservative Party to abandon any public hostility to Québec.

The controversy over secularism in provincial politics has also been addressed by the federal parties and demonstrates the need for parties to be careful in the way they approach Québécois interests. While the leaders of the Conservatives, Liberals and NDP all objected to Québec’s secularism legislation banning public sector workers from wearing religious symbols, none committed to helping court challenges against the legislation, including the NDP, whose leader, Jagmeet Singh, wears a turban as part of his own religious practice. The Liberals came the closest to suggesting that they might consider challenging the law but have not done so to date. This case illustrates the ways in which recognizing and giving space to the cultures of different minorities can be in tension.

Ethnoracialized Minorities

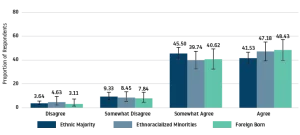

Canadian political parties also have strong incentives to be responsive to the interests of ethnoracialized minorities. The large foreign-born population, the high rate of immigrants’ citizenship acquisition and the concentration of ethnic minorities in swing constituencies mean that parties have to make efforts to win immigrant minority votes. Cross-partisan support for multiculturalism comes through in Figure 7.1, which captures party manifestos. It shows the percentage of statements made in opposition to multiculturalism in party manifestos subtracted from the percentage of statements supporting multiculturalism. The figure shows that,

over the past three decades, Canadian parties have been generally supportive of multiculturalism.

At no point over this period did statements in opposition to multiculturalism outnumber statements in support of it. There are periods in which the party manifestos are silent on multiculturalism, notably the Reform Party’s 1997 platform. Opposition to multiculturalism in the manifestos, however, is rare and in all but one case was outweighed by statements supporting multiculturalism. The exception is 2015 where Conservative manifesto statements opposing multiculturalism were equalled by statements supporting it.

Manifesto Project data provide a broad overview of party attitudes, but a more detailed look at party positions provides more nuance. The party with the strongest connection to ethnoracialized voters is the centrist/centre-left Liberal Party. The Liberals have drawn on their history as the party that adopted multiculturalism to make appeals to immigrant communities. They have consistently gained strong support from immigrant and ethnic minority communities. The Liberals have also consistently sought to ensure that minorities have been well represented amongst their candidates for office and in Cabinet appointments when they are in government. The Liberals appointed the first Chinese Canadian Cabinet minister in 1993 and had the first three South Asian Members of Parliament (MPs) elected to Parliament in the same election. After the 2015 election, the Liberals appointed four racialized MPs to Cabinet and added a fifth in 2017.

The social-democratic NDP has also attempted to win support in diverse communities. Although the party has been consistently supportive of multiculturalism, their support amongst immigrants and ethnic minorities has consistently trailed that of the Liberals. However, the NDP was the first major federal party to see a racialized minority person seek the party leadership (Rosemary Brown in 1975) and the first to select a racialized minority individual as leader when Jagmeet Singh won the party contest in 2017. In the 2021 election, the Green Party was also led by a member of a racialized minority, Annamie Paul.

The group of parties for which responsiveness to ethnoracialized minorities is most complicated are parties of the right and centre-right. Political imperatives have often forced the centre-right to take on positions supporting ethnoracial and cultural diversity. At the same, pressure from anti-immigrant and anti-multiculturalism voters have at times led some right parties to express hostility to either immigration or aspects of Canada’s multiculturalism policy. In the 1980s, the Progressive Conservative government expanded multiculturalism policy as part of an effort to appeal to ethnic minorities. In the 1990s, the sudden emergence of the populist Reform Party, which was opposed to multiculturalism, pulled conservatives away from a full embrace of diversity. In the 2000s, however, the various conservative parties merged to form the current Conservative Party, and the party once again sought to increase its support amongst ethnic minorities, especially voters with conservative views on fiscal policy and social issues. In government, the Conservatives issued formal apologies to recognize historic wrongs to many minority groups, including an apology for the head tax levied on Chinese immigrants from the 1880s to the 1920s.

Having said that, Conservative appeals to immigrants still do not automatically translate into enthusiasm for the multicultural approach to diversity.

Growing anti-Muslim sentiment on the right of Canadian politics nudged the Conservative into a less accommodating strategy.

Before the 2015 election, the Conservatives banned niqabs from citizenship ceremonies (later overturned in the courts), and during the election, they proposed a “cultural barbaric practices hotline” designed to encourage people to report practices that transgressed “Canadian values,” such as forced marriage. In general, Conservative efforts to win the votes of ethnoracialized groups have been highly segmented, with the party directing its appeals to social and fiscal conservatives among minority communities.

It is also worth noting that the 2019 federal election saw the emergence of a small right-wing populist party, the People’s Party of Canada, which advocates significant cuts to immigration levels and the abolition of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. While the People’s Party received less than 2 percent of the vote in 2019 and did not win a seat in Parliament, it more than doubled its vote count in 2021, receiving 4.9 percent of the popular vote but again failing to win a seat in Parliament. It is unclear whether the party will be strong enough to run competitive campaigns in future elections.

In most provinces, the dynamics around ethnoracialized minority representation play out in ways similar to the federal level. Large numbers of ethnoracialized minorities in swing ridings in provinces such as British Columbia and Ontario give parties a strong incentive to be responsive to the interests of ethnoracialized minorities. As we have seen, however, Québec is an exception. There is broad cross-partisan support amongst Québec’s provincial parties for placing restrictions on the religious symbols that Québec civil servants and those accessing provincial public services can wear.

Indigenous Peoples

Parties’ responsiveness to and representation of Indigenous Peoples has been the weakest of the three groups discussed in this report. The same electoral system dynamics that create incentives for parties to respond to the interests of Québécois and ethnoracialized minorities applies less to Indigenous Peoples, who make up a much smaller proportion of the Canadian population (about 4 percent). There are far fewer ridings with majority or plurality Indigenous populations. This, coupled with historically lower voter turnout in Indigenous communities, has meant that parties have been less responsive to the concerns of Indigenous Peoples than the concerns of Québécois and ethnoracialized minorities.

In recent elections, however, political attentiveness to Indigenous voters has increased. The combination of the Idle No More movement’s Rock the Vote Campaign and efforts by AFN’s Chief Perry Bellegarde to get Indigenous Peoples to vote led to an increase in Indigenous voter turnout from 47 percent in 2011 to 62 percent in 2015. There was a corresponding rise in representation of Indigenous candidates in the federal Parliament with 10 elected in 2015. The evidence on candidate recruitment suggests that parties are approaching Indigenous candidate recruitment in the same way they approach ethnoracialized minority candidate recruitment, with an emphasis on recruiting Indigenous candidates in ridings with large Indigenous populations.

Parties’ responsiveness to Indigenous Peoples on issues has also improved in past elections. In 2015, the main point of contention between the parties was how to respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on residential schools’ 94 recommendations, with the Conservatives promising to review the recommendations and Greens, Liberals and NDP committing to implement all 94 recommendations. The Greens, Liberals and the NDP also committed to calling an inquiry into MMIWG, which was set up by a Liberal government in 2016. In 2019, the Conservatives, Greens, Liberals and NDP all made commitments to reconciliation that varied from the dismantling of the Indian Act (Green Party), to fully implementing UNDRIP (the Liberals and the NDP), to developing an action plan in response to the report of the National Inquiry into MMIWG (the Conservatives). Both the Conservatives and Liberals, however, maintained that they would seek judicial review of the Canadian Human Rights’ Tribunal ruling that support for children’s services in Indigenous communities are inadequate.